+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

diff --git a/OSU.md b/OSU.md

new file mode 100644

index 00000000..2f62d214

--- /dev/null

+++ b/OSU.md

@@ -0,0 +1,139 @@

+## No Carrots No Sticks

+---

+#### Creating a Digital Humanities Consortium on a Shoestring

+---

+Kathleen Fitzpatrick // @kfitz // kfitz@msu.edu

+Ohio State University Digital Humanities Network

+29 November 2021

+

+Note: Thanks so much for having me join you today, and for asking me to talk a bit about how we established DH@MSU and the kinds of work we're doing here. So much of what's possible within the academy is highly local and institutionally specific, and so while I hope that what I'm going to share is of value to your thinking about how to move digital humanities forward at OSU, the question of its effectiveness comes with a big "your mileage may vary."

+

+

+

+

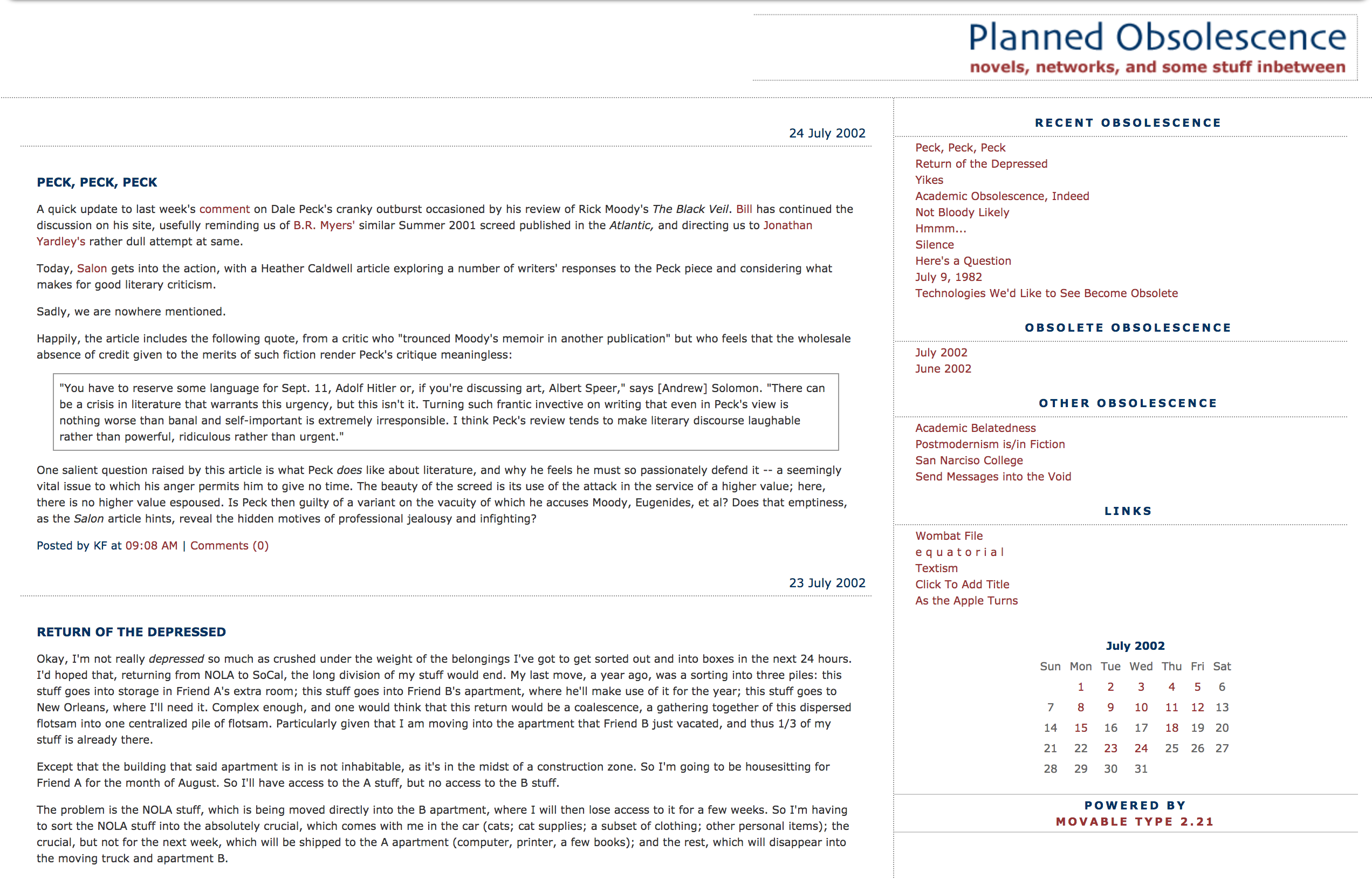

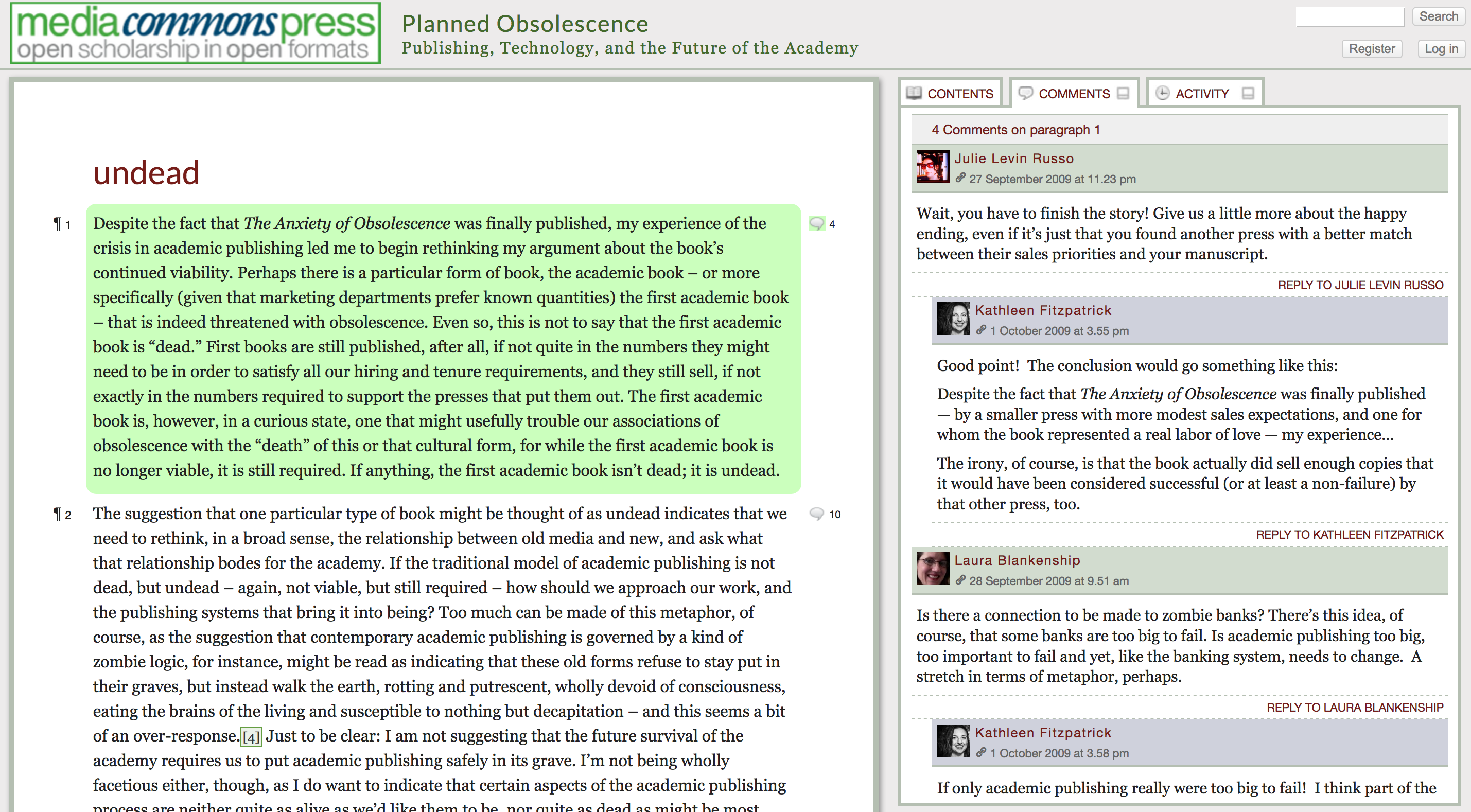

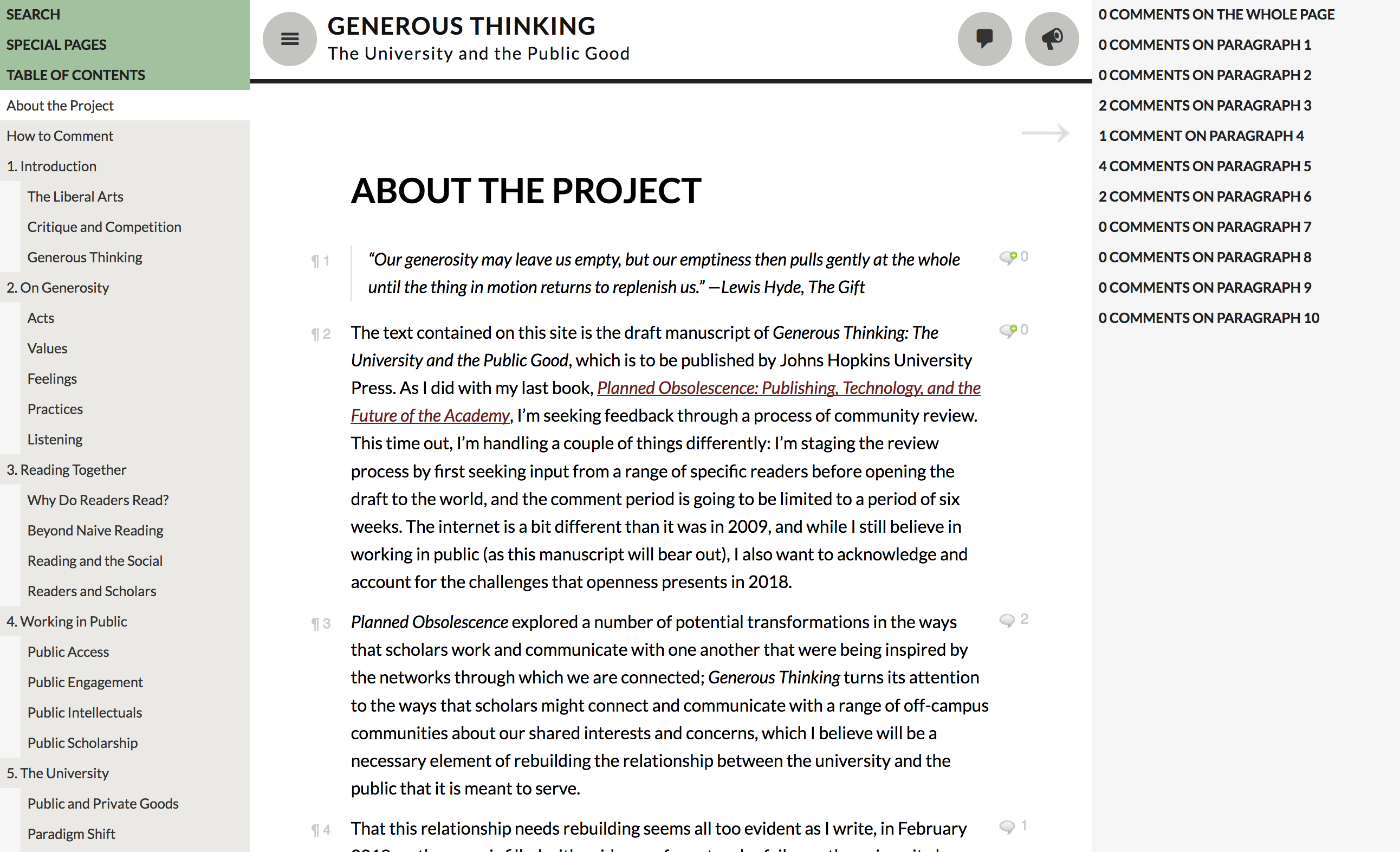

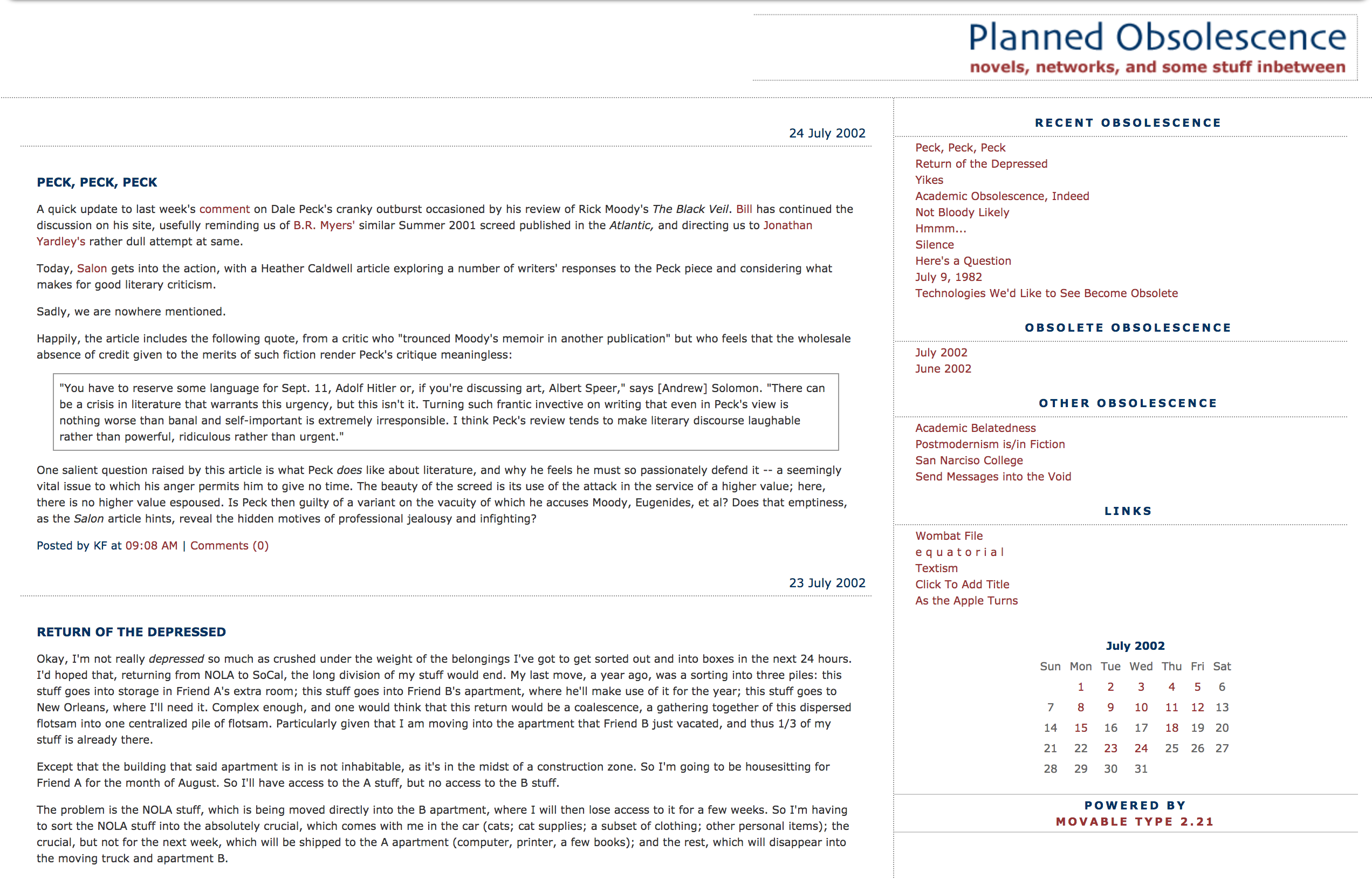

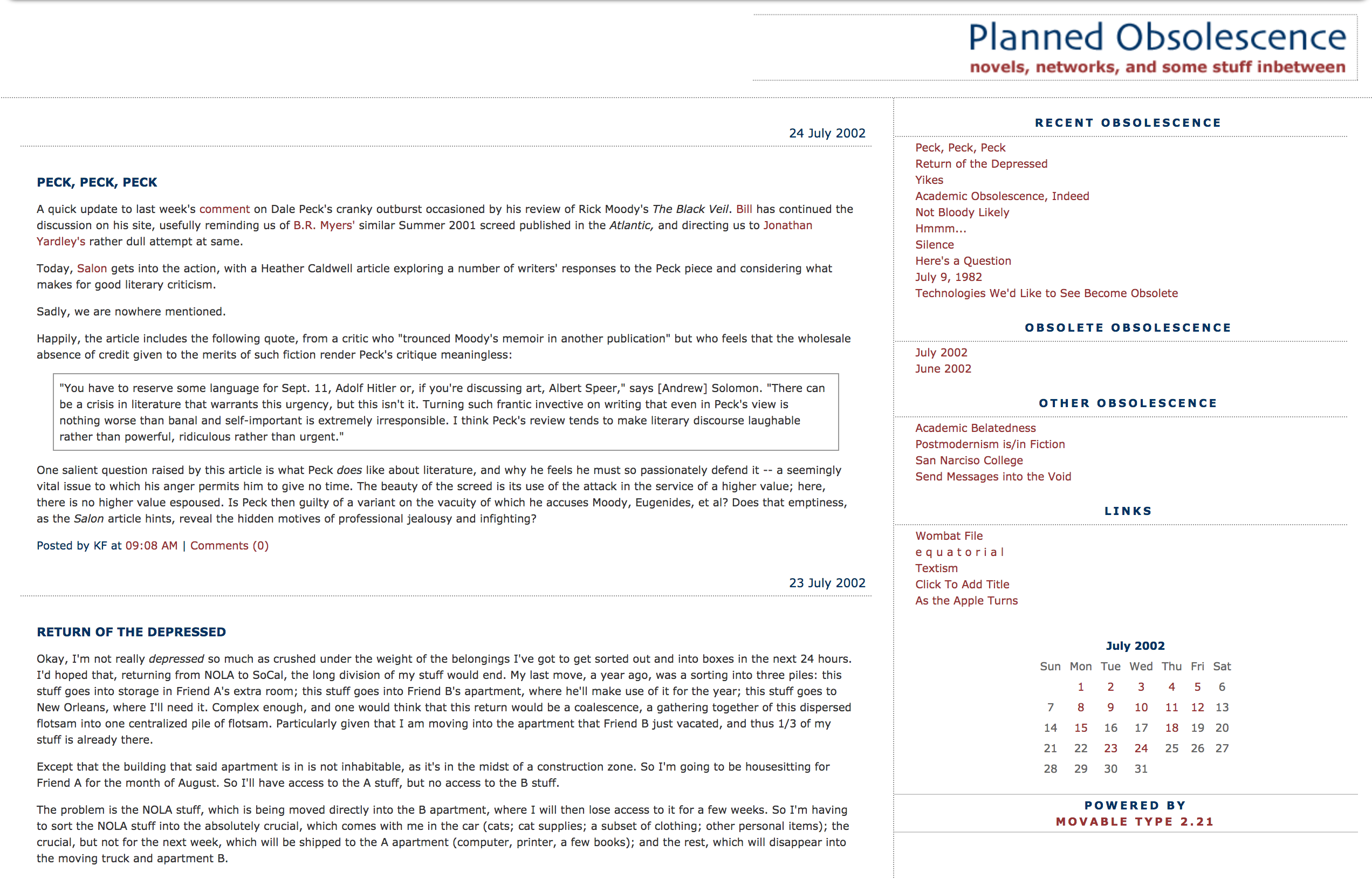

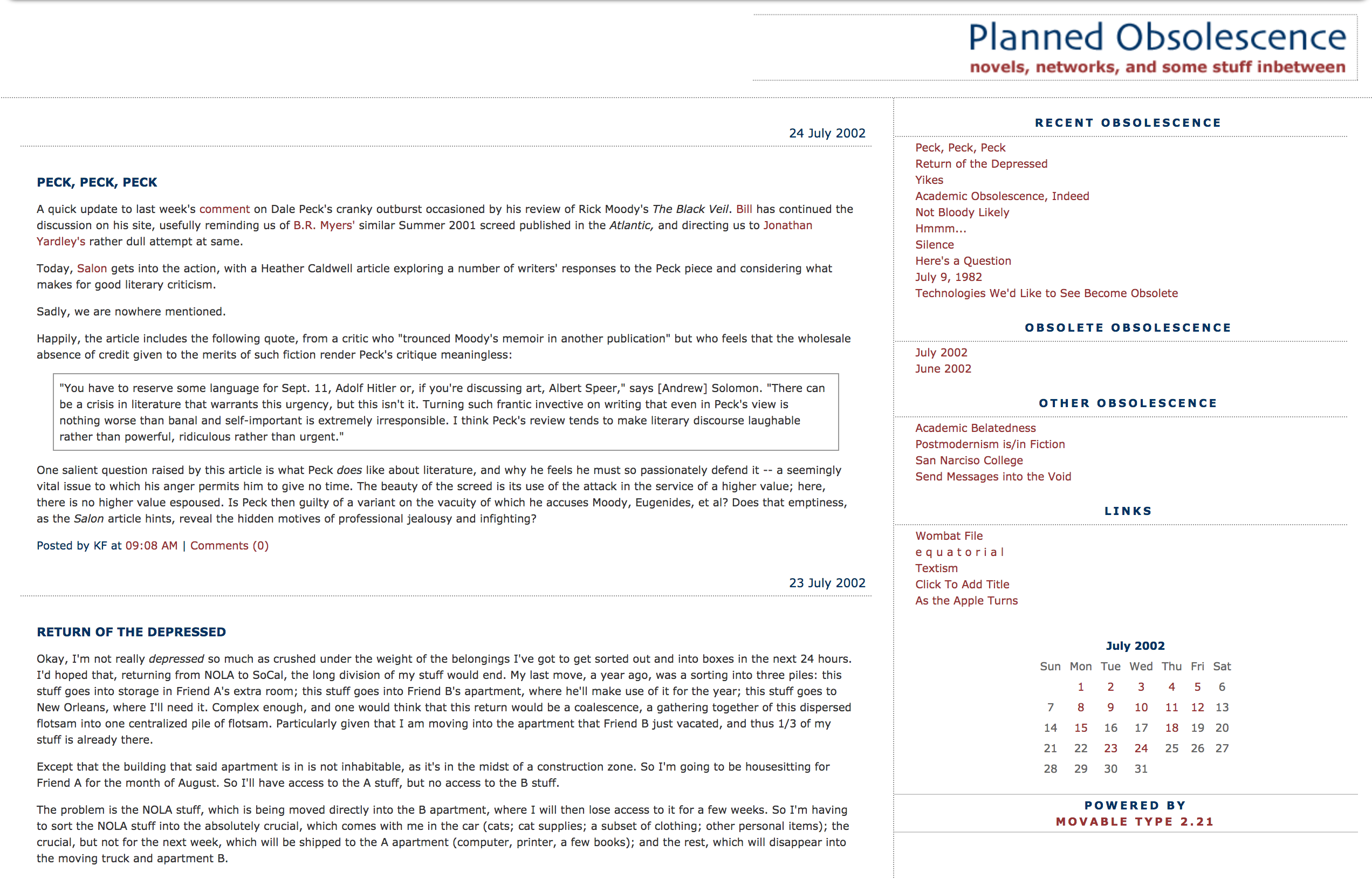

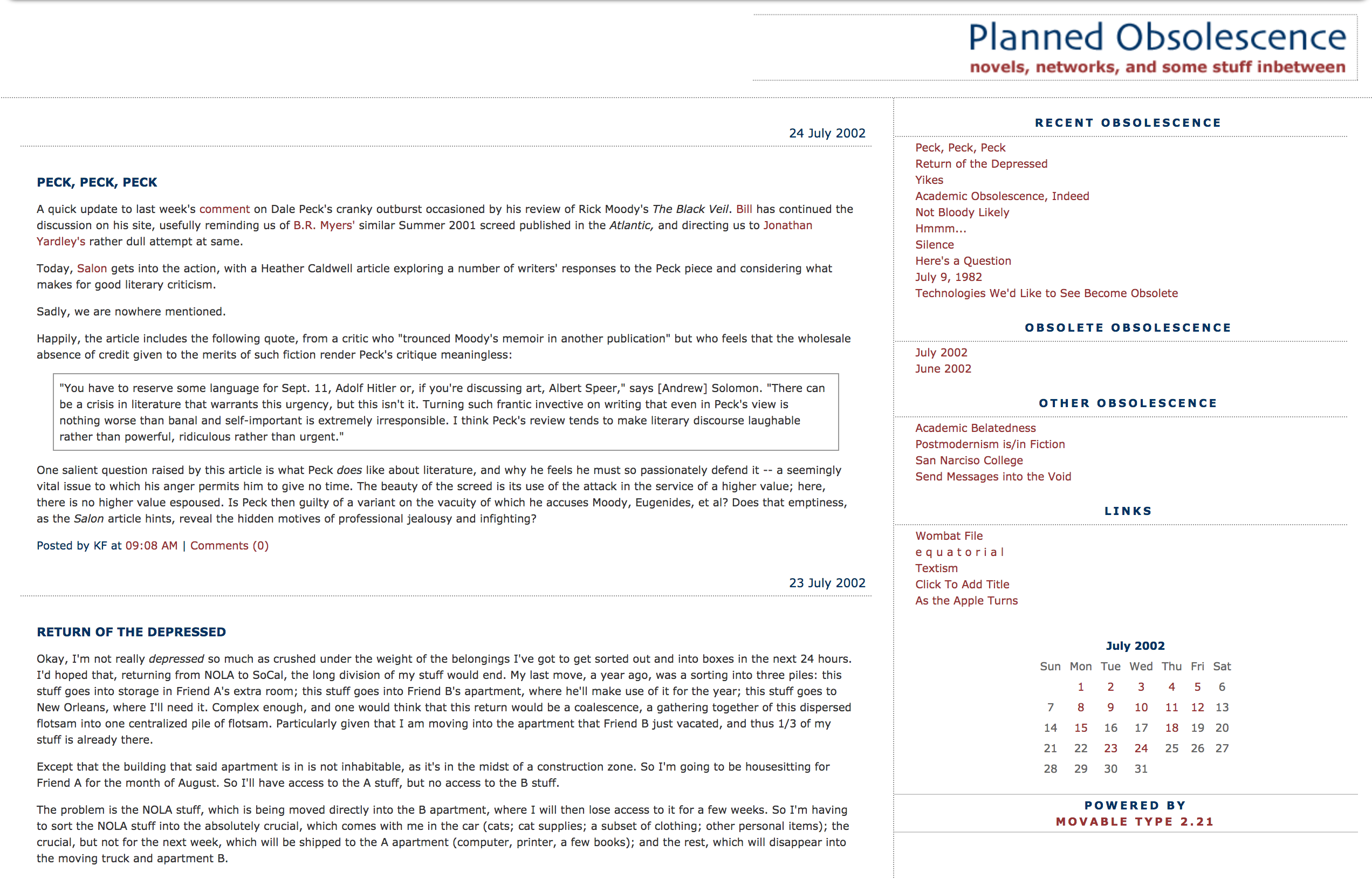

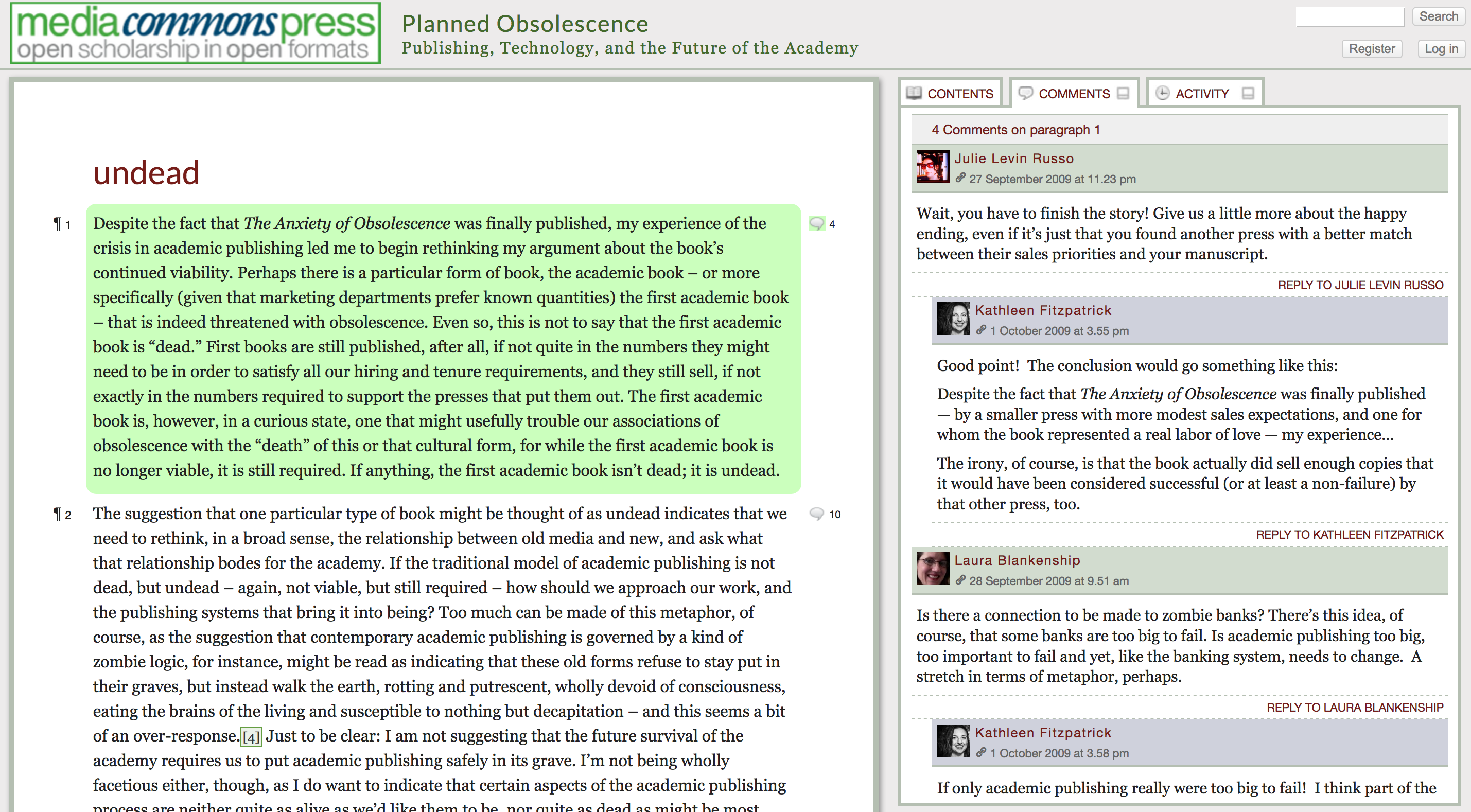

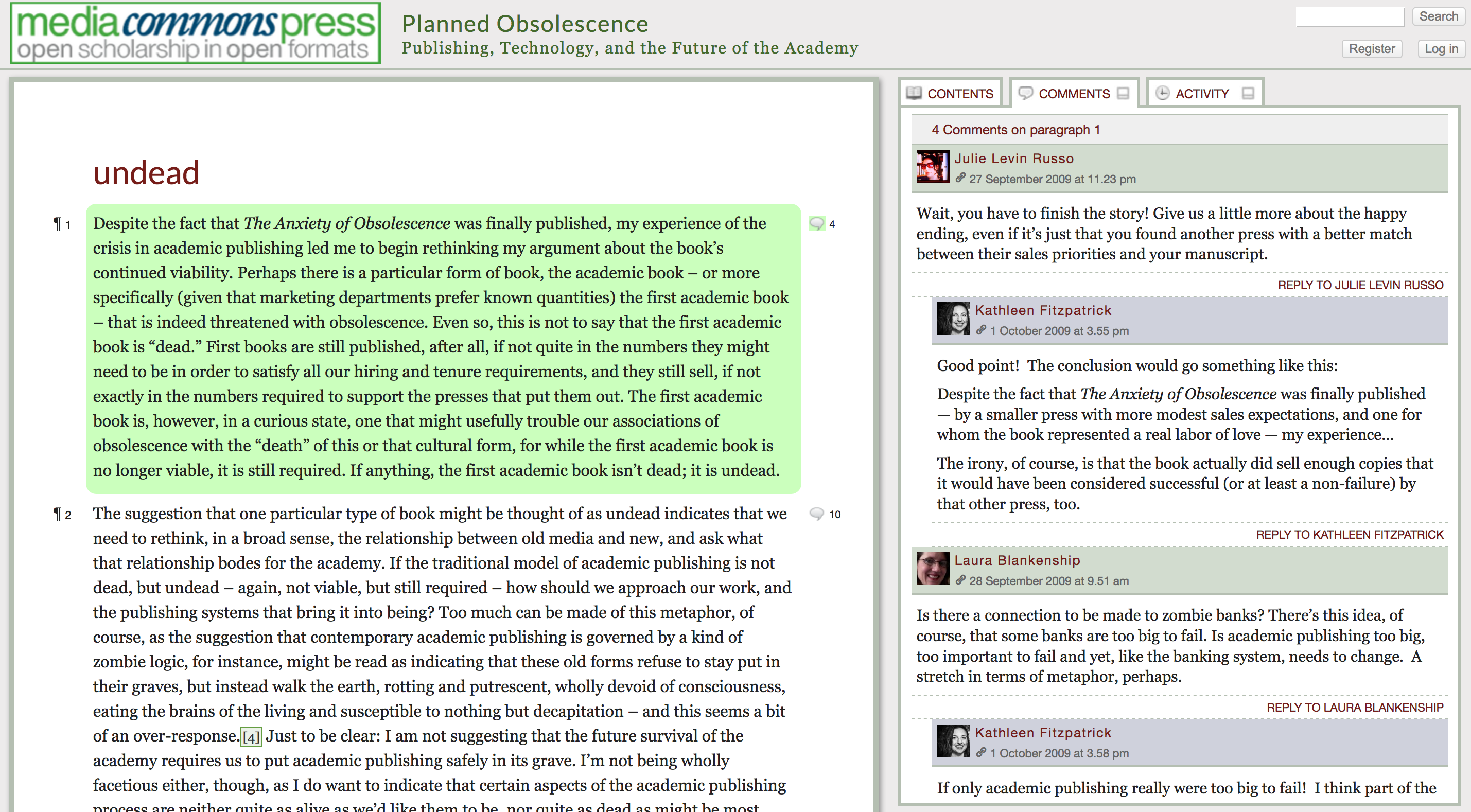

+Note: Perhaps the first thing to note about DH@MSU is that while it's a relatively new structure, what's going on under the hood is far from new. The digital humanities has a very long history at Michigan State, but for most of that history, it developed in idiosyncratic, non-institutional, and often personality-driven ways. I was brought to MSU in 2017 as the first official "Director of Digital Humanities" -- at least sort of; I'll backtrack on that in a little while. In any case, what I was asked to do was to raise the profile of digital humanities both within the university and on the national scene, not least by creating a sense of structure around it. But walking into a new institution where DH work has been done the way it has been done for more than 30 years and saying "I'm here to direct things!" is risky business, to say the least -- especially when the role of director comes with neither immediately available carrots nor any apparent sticks.

+

+

+

+

+Note: Backing up a bit: I came to this role from having been the associate executive director of the Modern Language Association (the largest scholarly society in the humanities), as well as the organization's first director of scholarly communication. I was hired into that role to help the organization think about the ways it might transform its publishing practices for an increasingly digital environment. And this is I guess the first true-confessions part of this talk: I had precious little idea how to do that. I had no real experience working in publishing (which I recognize may have been a bit of a benefit, if you're being brought in to transform established practices), and perhaps more importantly, I had no real experience managing people within an organizational structure. In my prior position, I'd directed a small interdisciplinary program at a small liberal arts college, and I'd worked to elevate that program to departmental status, and to make it not just interdisciplinary but intercollegiate. And in that vein I'd led the efforts to make the intercollegiate group into a functioning unit, bringing together in a productive way the disparate goals and perspectives of highly opinionated colleagues on five campuses with radically different cultures. So, leadership, sure. But management? Actually being the boss of people? Was a very different thing indeed.

+

+It's been an enormous benefit to me in my current role to have experienced up close the difference between management and leadership, and I have a lot more to say about that if you're interested. But the key thing to note here is that while good management focuses on bringing out the best in people in order to help a team optimize its processes and achieve organizational goals, changing those processes and goals and getting people on board with moving in a new direction requires a different set of skills. Management, after all, comes with both carrots, in the form of merit raises, and sticks, in the form of disciplinary action. Transformational roles within the academy very often come with neither. And I would be willing to bet that the number of faculty members anywhere who consider themselves to have a "manager" is vanishingly small. So convincing a bunch of free agents to work together in a focused way toward some kind of vision of change requires an entirely different kind of authority, one built on trust, on relationships, and on listening.

+

+When I was in the process of making the transition to MSU, a friend and I were talking about the new role I was going to take on. I described what I knew of it -- that I'd be the director of digital humanities, and that the dean who hired me was hoping that I could help increase the visibility of our DH program both within the university and on the national level. And my friend nodded a bit, and then said, "yes, but do you know what your job is?" I had to admit that, just as when I was starting at the MLA, I had only the most tenuous grasp on what it was I was being asked to do, and how exactly I would go about it. What does it mean to increase a program's visibility? What's required to make that happen?

+

+The one thing that I knew was that I needed a much deeper understanding of the institutional and interpersonal environment that I was entering, not least because, prior to interviewing for this position, this is what I knew about MSU's DH environment:

+

+

+

+

+Note: MATRIX, one of the oldest and most successful DH centers in the US, and LEADR, a lab that I knew had some kind of relationship with MATRIX, sort of, and that was mostly student-facing. As I moved into the interview process, I did enough research to figure out that

+

+

+

+

+Note: there was also an academic program in DH, offering both an undergraduate minor and a graduate certificate, but there was so much more I needed to know.

+

+

+

+

+Note: There were projects that I'd known for a long time, like H-NET, but had no idea they were housed at MSU. There were labs like the DHLC that I knew were there but didn't really understand and hadn't connected to the overall DH picture, and labs like WIDE that I hadn't known about. And there were new spaces and projects coming into being, including the Library's DSL and the College of Arts and Letters's CEDAR collaborative. And amidst this alphabet soup (which I'll unpack in a bit), the relationships among these units was not at all visible to me.

+

+My running joke for the first several months in the position was that my job consisted mostly of having coffee. I reached out to everyone that I could think of within the DH scene at MSU -- present and former directors and associate directors of these labs and centers, faculty with digital projects, administrators, and so on -- and set up time to chat. I asked each of them to tell me the story of the digital humanities at MSU -- how their center or lab or project came to be, how it fit in (or did not fit in) with the other such entities on campus, how it had evolved over time. I asked them what they felt was necessary to creating a more holistic environment for DH within the institution, and where they felt the chief roadblocks to such interconnection and collaboration lay. I also asked them who else I should be talking to, and then talked to them. And in the process worked with my brilliant assistant director, Kristen Mapes, to gather a list of everyone involved in digital humanities at MSU in order to call a meeting.

+

+

+

+

+Note: Ah, but wait! A little backtracking is again in order, as you may have noticed in that last sentence that I, as a brand new director of DH, and as in some senses at least the first director of DH, already had an assistant director. That wasn't her title yet -- she was officially "coordinator" of DH, if I recall correctly -- but Kristen Mapes had come to MSU three years earlier, in 2014, and had been working both to administer the academic program and to create community around DH. In that vein, she had been collaborating with a number of colleagues, both in the library and elsewhere on campus, to offer a wide range of workshops on digital methods and topics, and had been working with the previous directors to establish the goals and structures for the undergraduate minor and the graduate certificate program.

+

+Okay, but hang on -- if I was the first "director of DH," how were there previous directors? As it turns out, the academic program in digital humanities has its origins in early work done by Danielle DeVoss, a faculty member in (and now chair of) the department of writing, rhetoric, and American culture, and Scott Schopieray, then the director of academic technology and now the assistant dean for academic and research technology in the College of Arts & Letters. Danielle and Scott worked together beginning in 2008 to plan what was then called an undergraduate "specialization" in Humanities Technology, and Danielle brought together a larger group of faculty in 2011 to develop a graduate specialization in what was now being called Digital Humanities. An academic program needs a director, and Danielle took on that role from 2012 to 2015, creating much of the institutional structure around DH (including promoting the specializations to take on the status of an undergraduate minor and a graduate certificate program, shepherding the DH course code through the various bureaucratic processes, and establishing a minimal budget to support the program). In Fall 2015, however, Danielle began a year-long distinguished visiting position away from MSU, and so was succeeded for that year by Sean Pue; in Fall 2016, Sean began a two-year fellowship leave, and so was succeeded by Stephen Rachman. Each of these three directors took on the role as a service responsibility on top of their more usual workload, and each was compensated with a small administrative salary increment. During 2016-17, however, the dean of the college determined that DH needed a more stable directorate, one with administration as its primary focus, in order to develop a vision for bringing together the academic program with the extraordinary research being done across the university, with the goal of producing something perhaps a bit larger than the sum of its parts.

+

+And so, in August 2017, I arrived on campus and starting having a lot of coffee. And I read through whatever documents I was able to get my hands on, all with an eye toward understanding and appreciating the work that had gone into making DH at MSU what it had become, as well as the institutional and interpersonal challenges involved in making it something more. Those two things -- the institutional and interpersonal -- were deeply entwined, not least because while I'd been asked to get the existing labs and centers and projects and programs at MSU to cooperate and collaborate, I'd been given neither carrots nor sticks to make that happen. I couldn't offer tantalizing new resources that would make such collaboration appealing, nor did I have any authority to force the issue. I needed to get everybody on board without them having any particular reason to do so.

+

+This work of people-wrangling reminds me of the crucial argument made by Stephen Ramsay in his essay "Centers of Attention," originally published in the volume *Hacking the Academy,* which I've recently gotten to re-read in an expanded and revised form. In this essay, Steve begins from the conclusion that "centers are people," and encourages those who are longing for a center to coordinate and facilitate their work to begin there.

+

+

+

"I don't want to say that everything magically falls into place once you have formed the basic community of people and ideas, but it's staggering how all of the decisions that so obsess people trying to build a center follow logically and inexorably from the evolving needs and expanding vision of more-or-less informal gatherings of like-minded enthusiasts."

+

——Stephen Ramsay, "Centers of Attention"

+

+Note: As Steve would readily acknowledge, there's a lot of labor hidden between the phrases in this sentence, not least in "form(ing) the basic community of people and ideas" and in elucidating their "evolving needs and expanding vision." My round of coffees was one component in that process, but that mostly created one-to-one connections between me and my new colleagues. Forming a community required something different. So in September, I invited everyone that Kristen and I could think of to a community meeting to discuss the future directions for DH and to see what we might want to do together. If I'm remembering correctly, around 25 colleagues came to that meeting and discussed paths forward. In the course of all of those conversations it became clear that while lots of prior work had been done, there wasn't yet a connective structure within which this large group of people could make the potential for collaboration a part of their ongoing institutional lives, nor was there an institutional structure that could help facilitate the process of making those potential collaborations actual. So we collectively decided that one of our first orders of business should be developing a set of bylaws to define the parameters of our work together. Four volunteers came together with me over the course of a semester to draft a set of bylaws defining DH@MSU and the structures that would support and facilitate our community.

+

+

+

+

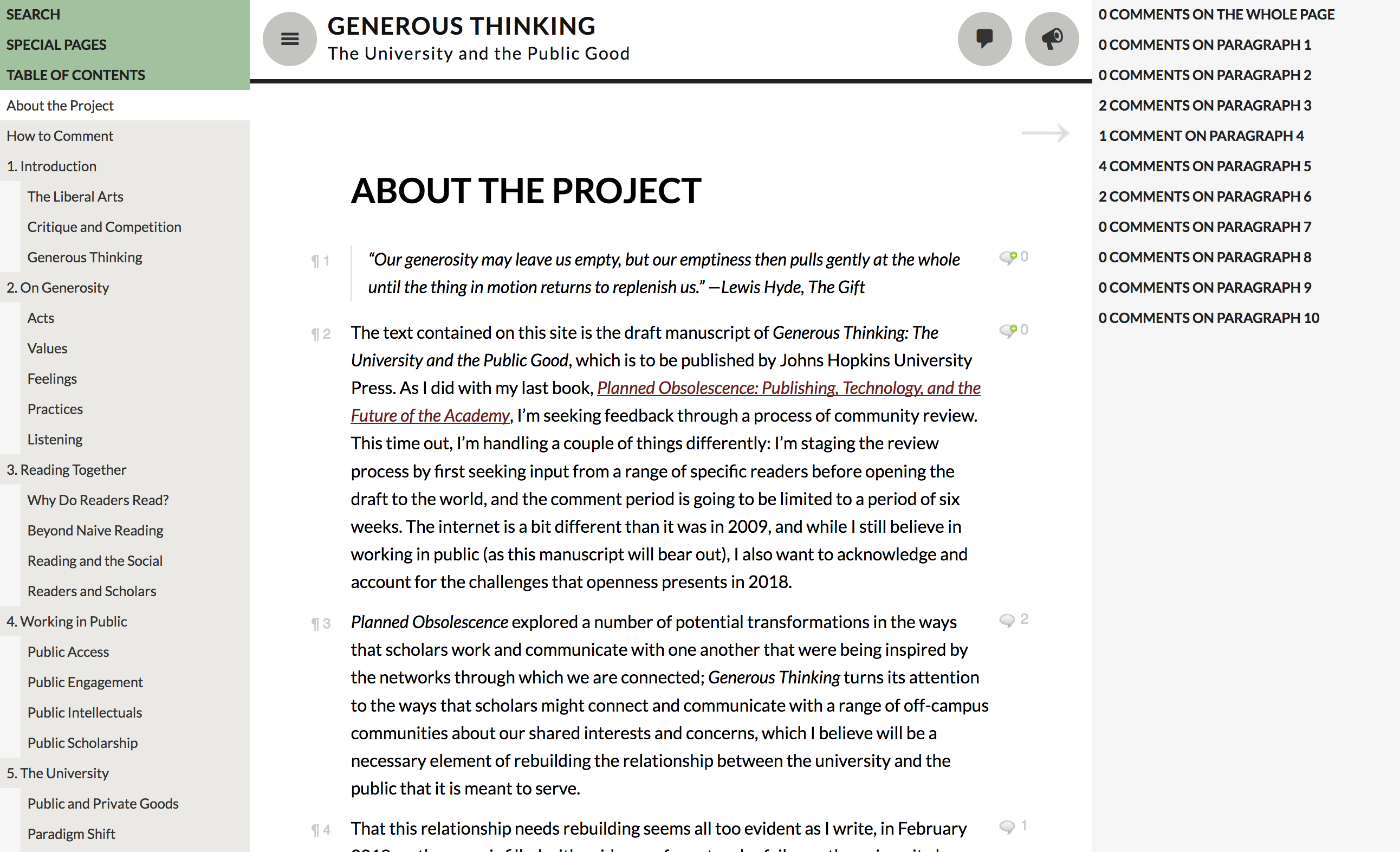

+Note: Bylaws give every appearance of being the the least idealistic genre in which one can write, all legalese and densely numbered sections and sub-sections preparing them to be cited in an array of procedures you should hope you never have to participate in. But they have the potential to be wildly idealistic as well, defining the best possibilities for our work together. In an orientation session for new academic administrators on campus, our then VP of Academic HR said of academic misconduct that "the worst behavior you are willing to accept is the best behavior you can expect" -- meaning that if you're willing to compromise your ethics or values in one situation, those standards remain compromised for others that follow. I believe the same about bylaws: they have to be written to define us at our best, because they set the standard for a lot of ensuing activity, and they define both who we are and how we want to work together.

+

+So the first, and perhaps most important task in our bylaws was that work of definition. We had the opportunity to define our community and our work as inclusively as possible, and in the process to create the best possible sense of who and what we wanted to be. And so our bylaws open by noting that

+

+

+> DH@MSU is both a research center and a program, based in the College of Arts and Letters but working across the colleges and units of the university.

+

+Note: READ SLIDE. This clause creates the possibility for collaboration outside the usual institutional silos, a necessary possibility given the next clause, defining the participating units in DH@MSU:

+

+

+> DH@MSU brings together the many programs, centers, labs, and other units working on digital humanities related projects and curricula. These units include but may not be limited to Digital Humanities within the College of Arts & Letters (CAL-DH), which houses an undergraduate minor and a graduate certificate program; the Critical Diversity in a Digital Age initiative (CEDAR); MATRIX; the Lab for the Education and Advancement in Digital Research (LEADR); Writing, Information, and Digital Experience (WIDE); H-NET; the Digital Publishing Lab (DPL); the Cultural Heritage Informatics program (CHI); the Digital Heritage and Literary Cognition lab (DHLC); the Digital Scholarship Lab; the Museums; the Libraries; and programs and departments across the College of Arts and Letters, the College of Social Sciences, the College of Communication Arts and Sciences, the College of Education, Lyman Briggs College, and the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities. These units retain their distinctive and independent governance structures and documents and come together voluntarily as DH@MSU.

+

+Note: A few things to note here: the DH minor and certificate programs are here defined as one of the units within the larger DH@MSU superstructure, thus placing that program alongside a wide range of other initiatives. We also explicitly name the range of colleges within which something that looks like "digital humanities" might be done, as well as the wide range of entities that were at that time doing it. These entities include of course centers like MATRIX and labs like LEADR (which supports digital research among undergraduate students in history and anthropology), but also projects like H-NET and the Cultural Heritage Informatics program, institutional spaces like the Libraries and the Museums, and more. More such entities have sprung up since these bylaws were approved, including my own research and development unit, MESH, and some of these entities have dissolved or changed their names, but with minor tweaks this paragraph remains an expansive vision of what DH@MSU encompasses.

+

+Even more important, however, is *who* DH@MSU includes. In section 2.1.1, we define our "core faculty" as

+

+

+> all persons holding the rank of professor, associate professor, assistant professor, instructor, librarian, specialist, or staff at MSU who have formal assignments or academic appointments in Digital Humanities

+

+Note: READ SLIDE. and in section 2.1.2, we include

+

+

+> other persons holding the above listed ranks, who maintain a research and/or teaching focus in the area of Digital Humanities, who participate in DH@MSU activities, and who request affiliation with DH@MSU

+

+Note: All of which is to say that (1) we understand the notion of "faculty" as broadly as possible, and we include colleagues whose primary roles differ from the usual teaching-and-research structure of those with titles like "professor," and (2) we welcome both those faculty whose positions have been written to include DH and those who have come to DH through other paths.

+

+

+

+

+Note: Having defined who we are, our bylaws go on to define how we'll work together, establishing our governance structures -- including our advisory, curriculum, research, and outreach and engagement committees -- as well as the composition and election of those committees and their spheres of responsibility. We also define the appointment, role, and review of the director of DH, as well as any assistant or associate director.

+

+There are some spots in which the process of reviewing the bylaws in order to present them to you has made me realize that we're not quite living up to them. For instance, we claim within the bylaws that a formal meeting of the core faculty is to be held once per semester, and we haven't held one of those in a few years, as there hasn't seemed much of anything that the faculty needs to discuss. We do, however, hold several events annually that are intended to bring the entire community together, including our THATCamps in August and January and our end-of-semester celebrations in December and April. But this moment of return to our governing document has encouraged me to wonder what initiatives we might press forward with if we were to meet more formally as a faculty.

+

+The key problem, of course, is time: especially now, after nearly two years of COVID, we're all overstretched, and the idea of adding one. more. meeting. is just more than most of us can bear. We're already facing a bit of fray in our governance fabric, as it is: all of our core faculty have primary appointments elsewhere, and the time they give us is an extra bit of labor. That they give it demonstrates their real commitment to DH@MSU and what it can do, but that commitment of necessity comes at the end of a long list of other commitments. And if I'm being honest, something similar is true of me: though my appointment is 40% administration, that 40% can only be spread so thin. As a result, most of our initiatives have been slower to develop than I'd like, but we're inching toward them. Key among those initiatives is developing a map of sorts for DH@MSU.

+

+

+

+

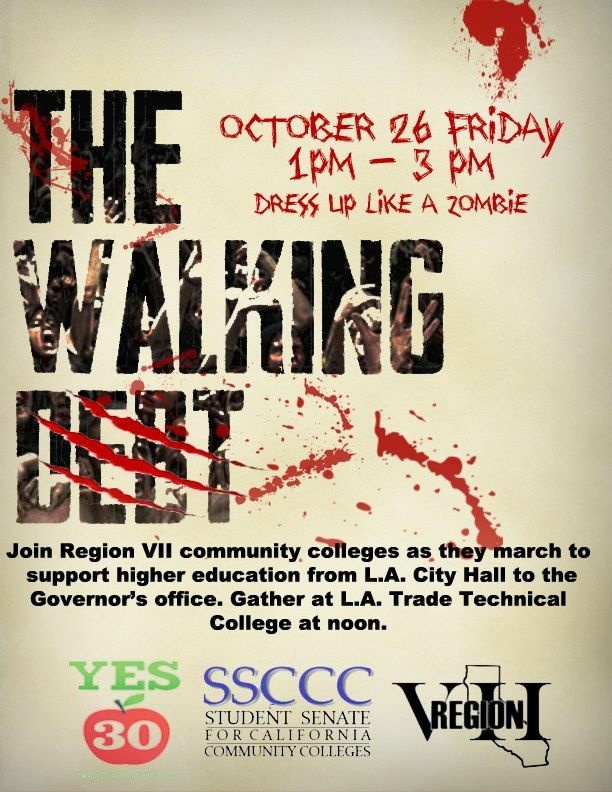

+Note: When we first created the structures within which we now operate, DH@MSU looked something like this -- we'd recently added three new units to our confederation: the DSL, or Digital Scholarship Lab, a fantastic space in the main library dedicated to the support of digital scholarship across the curriculum; CEDAR, a not-quite-acronym for the Consortium for Critical Diversity in a Digital Age Research, a group of faculty who joined the College of Arts & Letters as part of a cluster hire and are working collaboratively on critically engaged digital research; and my own R&D unit, MESH, which is not an acronym at all but is meant instead to be a complement to MATRIX, focusing on the future of digital scholarly communication. All of these projects and spaces were created in order to fill gaps in the DH landscape at MSU, to provide more support for more kinds of work being done across the field. But there are still institutional puzzles to be solved, especially for relative newcomers. For instance, if I have a project and I want to hire a student or two to work on it with me, where might I find funding for that? And how do I hire that student? If I need a higher level of developer support, is there a group of developers somewhere that I can work with? It's these kinds of questions that often drive the desire for formal centers, but as you can see we've got a pile of centers and still can't fully meet the need. Some of these centers, like MATRIX and the DHLC, are focused on internally generated grant-funded projects and aren't able to support projects that are brought to them. Some, like the DSL, have constituencies that are so broad that they cannot go deep on many projects. And all of them face similar questions about the full lifecycle of projects: How are they incubated? How do they get past the incubation stage and into full development? How can their teams obtain not just the funding but also the training they need to be self-sufficient? How are projects hosted and maintained over the long-term? And once those projects are no longer viable, what provisions can we make for flattening and archiving them?

+

+

+

+

+Note: In order to answer these questions, and more, we're currently working on two fronts: first, to map all of the resources within MSU that the DH community should know about -- the funding sources, the training opportunities, the support services, and more. And second, we're working to pull together the research units within DH@MSU with the other units on campus -- like EDLI, the Enhanced Digital Learning Initiative -- that have some of the same questions. We're hoping to build out additional layers of consortium, first, within the humanities and social sciences via what we're currently calling the Consortium for Digital Scholarship and Practice, and second,

+

+

+

+

+Note: across the university via the Research Facilitation Network, bringing together related groups in quantitative fields, in the bench sciences, and in university-level enterprise computing.

+

+

+

+

+Note: Okay, so we've now zoomed out from the constellation that is DH@MSU to the galaxy that is the Research Facilitation Network. And I've told you a whole lot about my journey along the way. But I'm guessing you might like me to boil this down into a few actionable ideas as you move forward with your own work here. So:

+

+

+1. Remember Steve Ramsay's claim -- centers are people -- but focus on the connections among those people.

+

+Note: READ SLIDE. Getting DH@MSU to where it is, and pushing it along to where it needs to be, is all about building relationships among the different folks with a stake in the collaborations that we hope to facilitate. Along which lines:

+

+

+2. Informal relationships are a great place to begin, but formal structures for those relationships can make them institutionally durable.

+

+Note: READ SLIDE. How can you define connections among independent units and projects that allow them to maintain their independence while leveraging their combined strength? This is especially important when you're trying to do the work of creating something coherent without a substantial budget or a top-down administrative mandate. And finally:

+

+

+3. Networks might facilitate the development of new, spontaneous connections in ways that centers cannot.

+

+Note: READ SLIDE. Networks can both harness the power of informal relationships and allow their impact to extend outward, drawing strength from the combination of resources and knowledge that all of their participants bring to bear. Networks are also more flexible than centers, in that they can accommodate new developments, shifts of direction, and so on in ways that solid structures cannot.

+

+

+## thank you

+---

+ Kathleen Fitzpatrick // @kfitz // kfitz@msu.edu

+

+Note: So: that's pretty much all the advice I've got right now, and I'm sure I've opened up way more questions than I've answered, so why don't we turn to your thoughts at this point? Thanks again for having me here.

diff --git a/README.md b/README.md

index db584dc1..4d4952ae 100644

--- a/README.md

+++ b/README.md

@@ -1,50 +1,2 @@

-

-

-reveal.js is an open source HTML presentation framework. It enables anyone with a web browser to create beautiful presentations for free. Check out the live demo at [revealjs.com](https://revealjs.com/).

-

-The framework comes with a powerful feature set including [nested slides](https://revealjs.com/vertical-slides/), [Markdown support](https://revealjs.com/markdown/), [Auto-Animate](https://revealjs.com/auto-animate/), [PDF export](https://revealjs.com/pdf-export/), [speaker notes](https://revealjs.com/speaker-view/), [LaTeX typesetting](https://revealjs.com/math/), [syntax highlighted code](https://revealjs.com/code/) and an [extensive API](https://revealjs.com/api/).

-

----

-

-Want to create reveal.js presentation in a graphical editor? Try . It's made by the same people behind reveal.js.

-

----

-

-### Sponsors

-Hakim's open source work is supported by GitHub sponsors. Special thanks to:

-

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

diff --git a/aiea.md b/aiea.md

new file mode 100644

index 00000000..073aa18f

--- /dev/null

+++ b/aiea.md

@@ -0,0 +1,166 @@

+## Generous Education

+---

+### Critique, Community, Collaboration

+---

+##### Kathleen Fitzpatrick // @kfitz // kfitz@msu.edu

+##### http://kfitz.info/presentations/aiea.html

+

+Note: Thank you, etc.

+

+

+

+

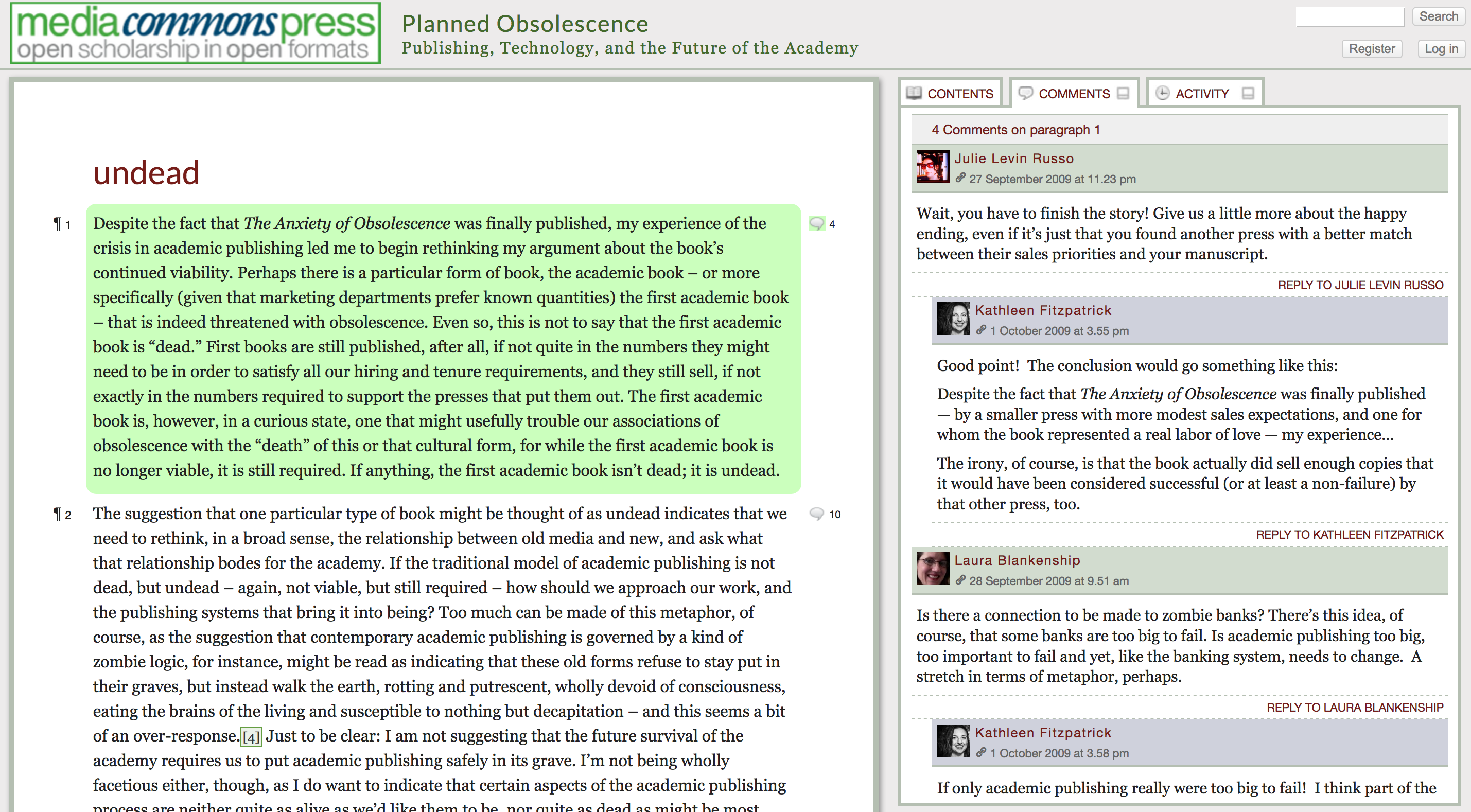

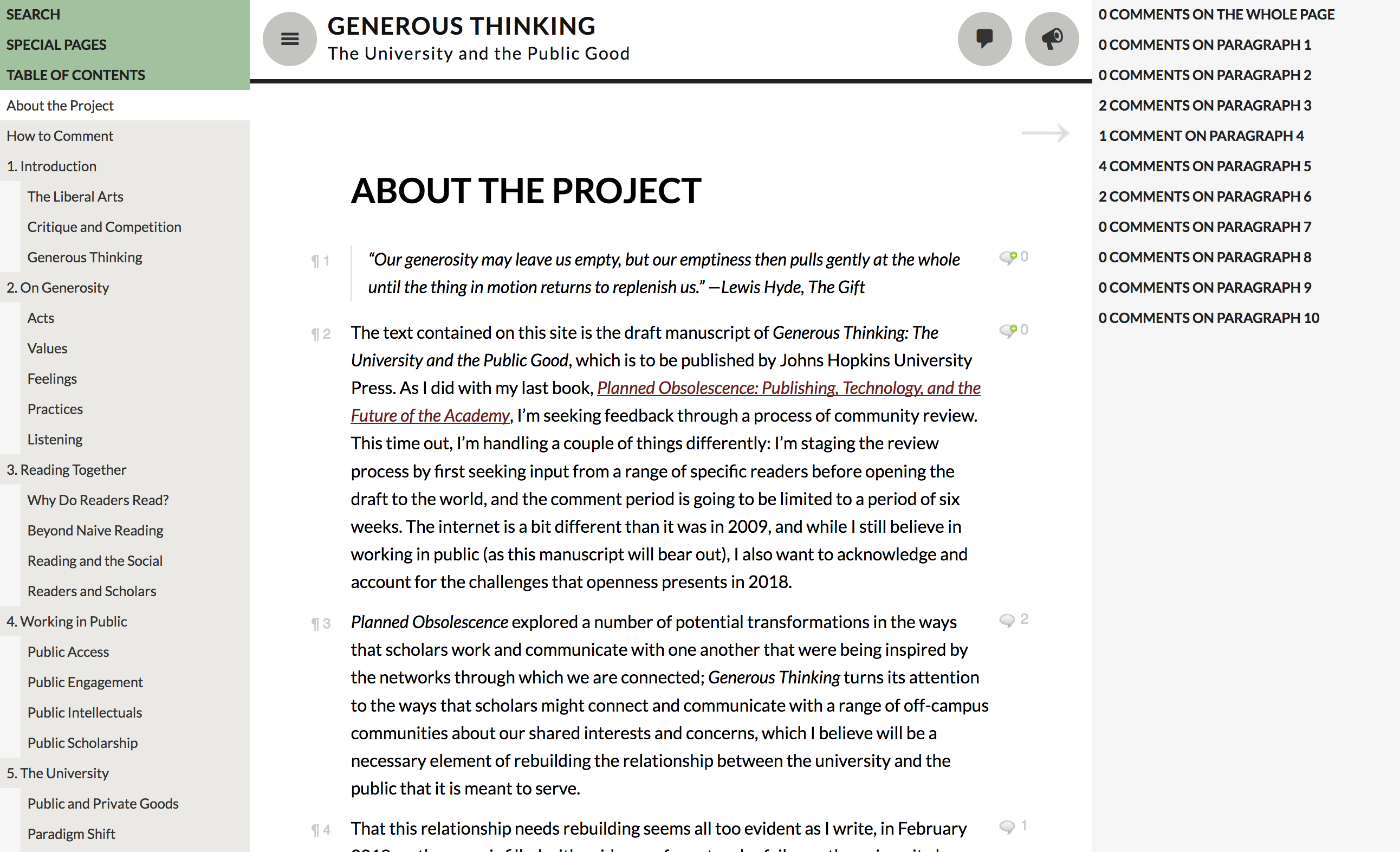

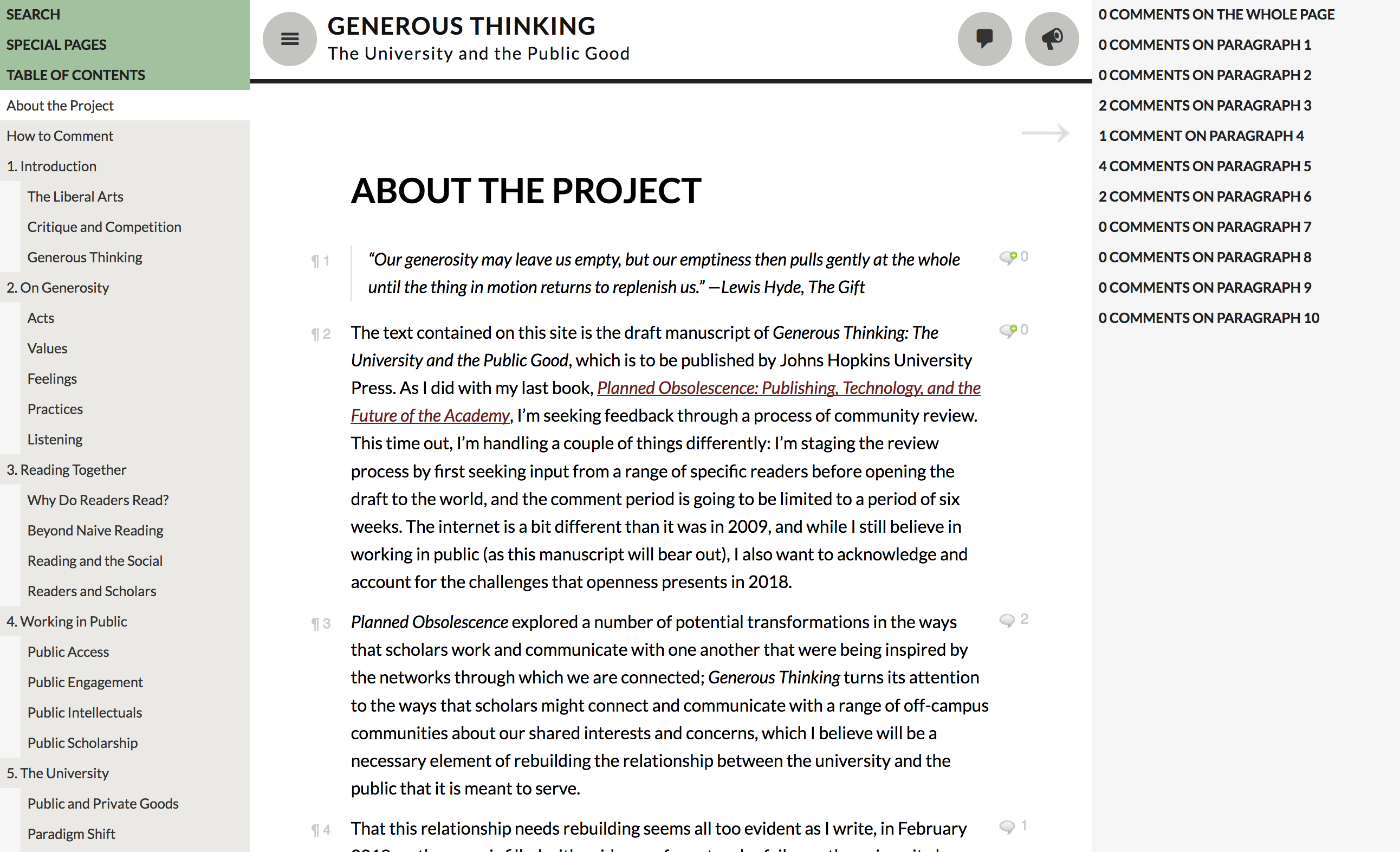

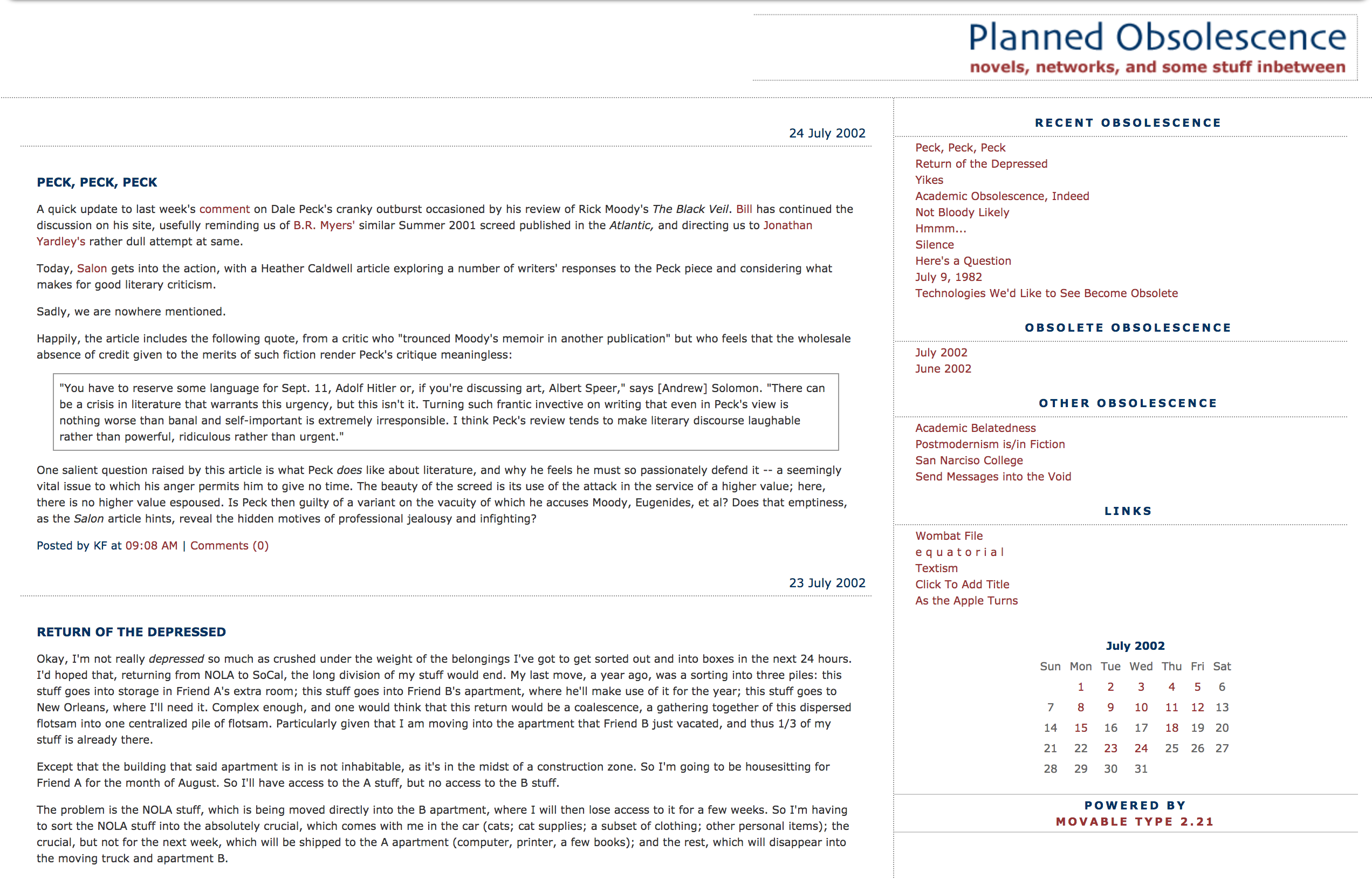

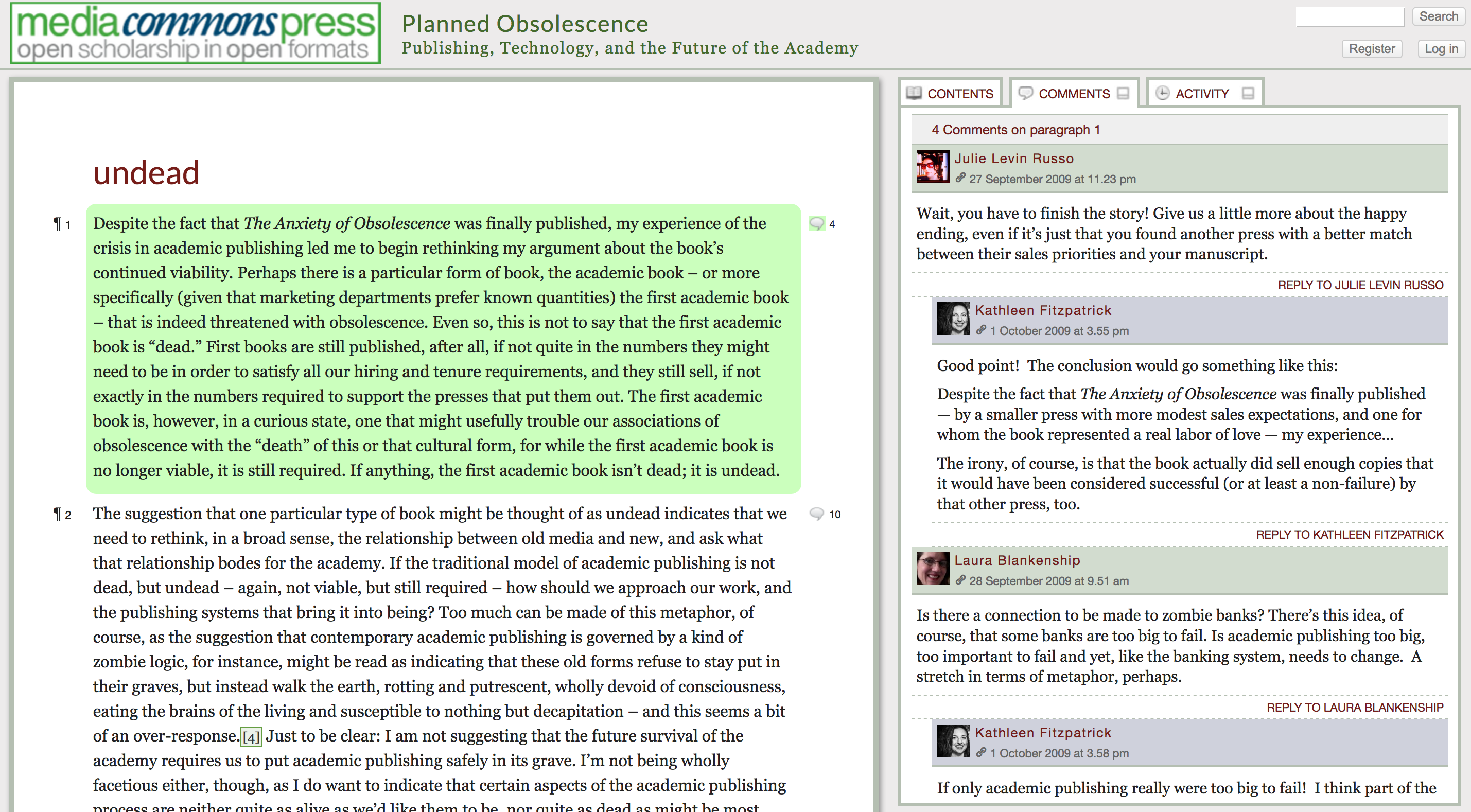

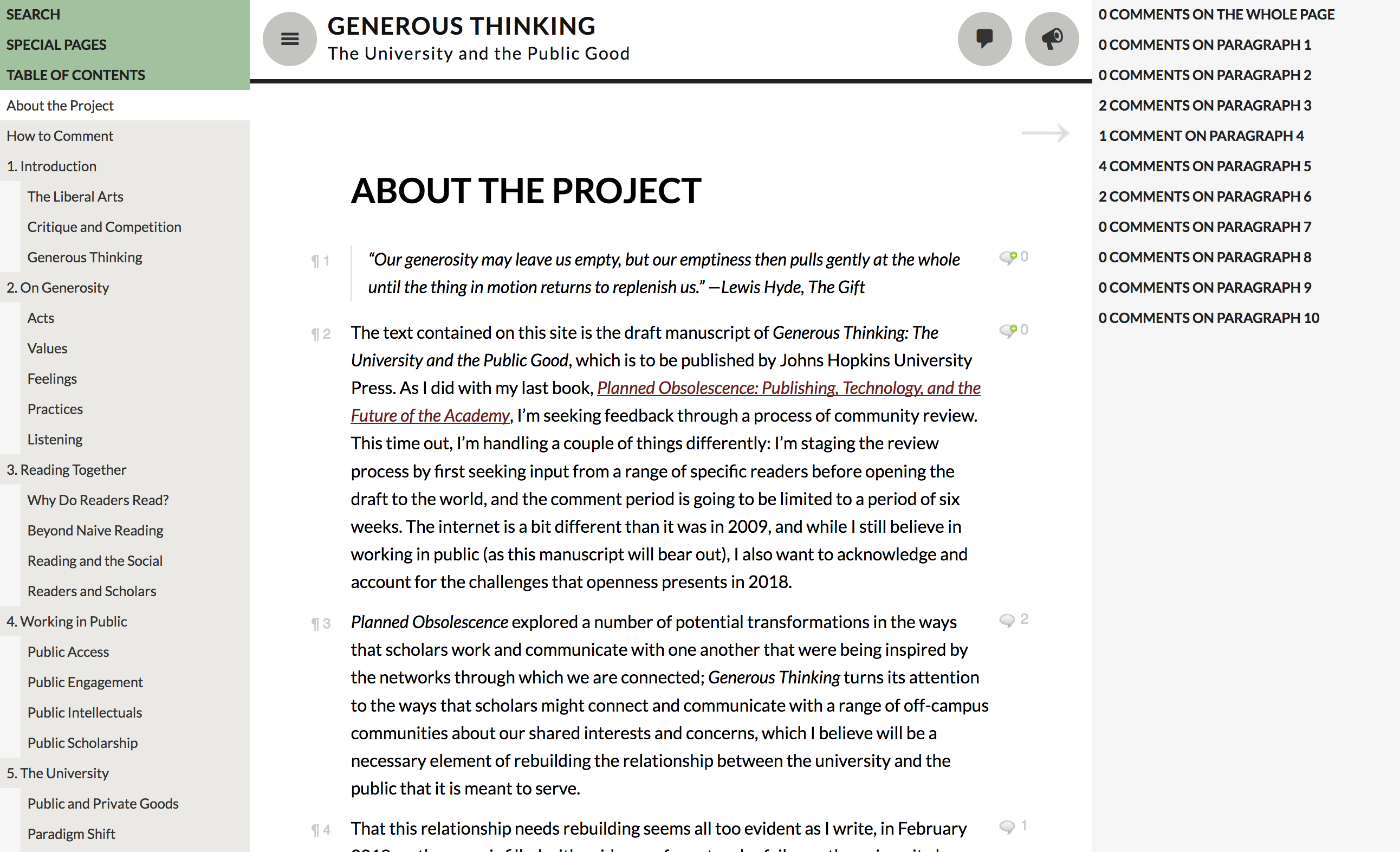

+Note: Much of what follows builds on the arguments in my recent book, _Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University_. The 'saving the university' part of the book's subtitle has to do with my growing conviction that the survival of institutions of higher education -- and especially _public_ institutions of higher education in the United States -- is going to require those of us who work on campus to change our approach to the work we do within them, and the ways we use that work to connect the campus to the many publics, from the local to the global, that it serves.

+

+

+# "radical approach"

+

+Note: The 'radical approach' part grows out of my increasing sense that the necessary change is a HUGE one, that it can't be made incrementally, that instead it requires -- as Chris Newfield notes in the conclusion of _The Great Mistake_ -- a paradigm shift, because there is no route, no approach, no tool that can readily take us from where we are today to where we need to be. As Tressie McMillan Cottom has noted of the crisis that she has seen growing in higher education today,

+

+

+> "This is not a problem for technological innovation or a market product. This requires politics."

--Tressie McMillan Cottom, _Lower Ed_

+

+Note: "This is not a problem for technological innovation or a market product. This requires politics." The problem, after all, begins with politics: the American public university that not too long ago served as a highly accessible engine of social mobility, making a rich liberal-arts based education broadly available, has been utterly undone. We are facing today not just the drastic reduction in that institution's affordability but an increasing threat to its very public orientation, as rampant privatization not only shifts the burden of paying for higher education from the state to individual students and families, but also turns the work of the institution from the creation of a shared social good -- a broadly educated population ready to participate in public affairs from the local to the global -- to the production of market-oriented individual benefit.

+

+

+

+

+Note: And all the while, we are also facing what Inside Higher Ed recently reported as "a larger than typical decline in confidence in an American institution in a relatively short time period." And this falling confidence cannot be simply dismissed as evidence of an increasingly entrenched anti-intellectualism in American life -- though of course, without doubt, that too -- but rather must be understood as evidence that, as I argue in the last chapter of _Generous Thinking_, higher education has for the last several decades been operating simultaneously under two conflicting paradigms -- on the one hand, an older paradigm, largely operative within the academic community, in which the university serves as a producer and disseminator of knowledge; and on the other hand, a more recent one, in which the university serves as a producer and disseminator of market-oriented credentials. Even worse than the conflict between these paradigms, however, is that both of them are failing, if in different ways. If our institutions are to thrive in the decades ahead we must find a new way of articulating and living out the value of the university in the contemporary world.

+

+

+# generous thinking

+

+Note: The book overall makes the argument that rebuilding a relationship of trust between the public university and the public that it ostensibly serves is going to require regrounding the university in a mode of what I refer to as "generous thinking," focusing its research and pedagogical practices around building community and solidarity both on campus and across the campus borders. It's going to require concerted effort to make clear that the real good of higher education is and must be understood as social rather than individual.

+

+

+# listening

+

+Note: So the book asks us to think about how we work with one another on campus, and how we connect our campuses to the publics around us. It begins by understanding generosity as a mode of engagement grounded in listening to one another, and to the publics with whom we work, attempting to understand their concerns as deeply as possible before leaping forward to our critiques and solutions.

+

+

+# reading together

+

+Note: The book goes on to explore ways that the critical reading practices we enact on campus might be opened up to foster greater engagement between scholars and other readers, creating means for those readers to see more of the ways that scholars work and the reasons for those methods, as well as for scholars to learn more about why general interest readers read the ways they do, building key bridges between two communities that too often seem to speak past one another.

+

+

+# working in public

+

+Note: I also spend time thinking about ways (and reasons) that scholars might do more of their work in public, publishing in openly accessible venues and in more publicly accessible registers, and developing more community-engaged research, in order to bring the university's resources to bear in helping work through community concerns, as well as to transform those communities from passive recipients of the university's knowledge into active collaborators in shared projects.

+

+

+# the university

+

+Note: But if we are going to make the kinds changes I argue for in the ways that scholars work, both on campus and off, the university as an institution must undergo a fairly radical transformation, becoming the kind of institution that supports rather than dismisses (or in fact actively punishes) collaboration and community engagement. The university must become the kind of institution that can focus less on individual achievement, on educating for individual leadership, and that instead focuses on building community, and indeed on educating for community-building. And this, perhaps needless to say, will require rethinking a lot about the ways we engage with our students.

+

+

+# students

+

+Note: Our students, after all, are our first and most important point of contact with the publics we serve. Our students come to us from an increasingly wide range of backgrounds and with a correspondingly wide range of interests. Ensuring that we connect with them, that we work with them in creating the university's future, is job one. But I want to suggest that some of our students are learning habits of mind from us that ultimately work to undermine the future that we want to build.

+

+

+# seminar

+

+Note: Here's the scene that first got me thinking in this direction, a moment in a graduate seminar I taught years ago, a moment that for me came to feel emblematic of the situation of the contemporary university. I want to preface the story by saying that I offer it not as an indictment of the kids today, but rather of the m.o. of higher education since the last decades of the 20th century. So here's the scene: the seminar is in cultural studies, and is meant to provide an overview of some current questions in critical theory. I do not now remember what article it was we'd read for that class session, but I opened our discussion by asking for first responses. And three students in a row issued withering takedowns of the article, pointing to the author's methodological flaws and ideological weaknesses. After the third, I said okay, that's all important and I definitely want to dig into it, but let's back up a bit: what is the author's argument here? What is she trying to accomplish?

+

+

+# silence

+

+Note: Nothing. "It's not a trick question," I said. "What is this article about?" Now, I was a fair bit younger and less sure of myself at that point, and I immediately began wondering whether I'd asked a stupid question, whether the sudden failure to meet my gaze was a sign that I, like the author, was now being dismissed as having pedestrian interest in neoliberal forms of meaning-making that demonstrated my complicity with the systems of oppression within which I worked. But it gradually dawned on me -- and then was confirmed over the course of the semester -- that the problem with the question wasn't its stupidity but its unfamiliarity. The students were prepared to dismantle the argument, but not to examine how it was built.

+

+

+# they say / i say

+

+Note: The students in this seminar, like so many of us, had learned all too well one of the lessons often extrapolated from Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein's _They Say, I Say_: that the key move in academic argumentation is from what others have previously said to one's own -- almost always contrasting, and inevitably more interesting or correct -- contribution. That is to say, that the goal of critical thinking is to expose the flawed arguments of others in order to demonstrate the inherent rightness of our own.

+

+

+# conversation

+

+Note: The larger point that Graff and Birkenstein make in _They Say, I Say_ is in fact a good and important one: that scholarship proceeds through conversation, and thus that scholarly argument begins with engaging with what others have said and then develops through one's own individual contribution to the discussion. The problem, however, is two-fold. The first part is that we are -- and when I say we, I mean human beings at this hour of the world -- we are by and large TERRIBLE at conversation. Witness any set of talking heads on television, or any Thanksgiving dinner table, or any department meeting: more often than not, we spend the time when other people are talking waiting for our own turn to speak, and we take what's being said to us mostly as a means of formulating our own response. We do not genuinely *listen*, but instead *react*. And the same is too often true of scholarly conversation: the primary purpose of engaging with what "they" have said is to get to the important bit -- what I am saying.

+

+

+# individualism

+

+Note: That's the first problem. The second is the assumption that what I am saying, my own individual contribution to the discussion, is genuinely individual, that it is my own. In no small part this stems from the hyperindividualistic orientation of the contemporary university -- an orientation inseparable from the individualism of the surrounding culture -- in which the entire institutional reward structure, including grades, credits, honors, degrees, rank, status, and every other form of merit is determined by what I individually have done. Every tub sits on its own bottom, in other words, and if I am to succeed it must be based on my own individual accomplishments -- even in those fields that most claim to prize collaboration.

+

+

+# zero-sum

+

+Note: Add to that the situation of most institutions of higher education today, in which austerity-based thinking leads us to understand that merit is always limited, and thus your success, your distinction, your accomplishments can only come at my expense. We all find ourselves in an environment in which we have to compete with one another: for attention, for acclaim, for resources, for time.

+

+

+# competitive thinking

+

+Note: As a result, the mode of conversation promoted by _They Say, I Say_ has become less about the most important forms of critical thinking on which our work focuses -- engaging with what has been said before us and adding to the discussion -- than about competitive thinking. Competitive thinking is a hyperindividualistic mode of debate that suggests that we are in an endless struggle with one another, in which there is only room for so much success, for so much attention. In competitive thinking, the pursuit of academic and professional success requires us to defend our own positions, and attack others. We're trapped on a quest for what Thorstein Veblen described as "invidious distinction," in which we separate ourselves from others by climbing over one another.

+

+

+# institutions

+

+Note: It's important to note that this situation applies as much to institutions as to the individuals who work within them. Insofar as the institutional reward structures within which we operate privilege achievement through competition, it's because our institutions are similarly under a mandate, as Chris Newfield has said, to "compete all the time." And it's only when our institutions separate themselves from quantified metrics for excellence that pit them against one another that we'll likewise be able to move fully away from competitive thinking and into a mode that's more productive.

+

+

+# teaching

+

+Note: But in the meantime, one of the places where we can begin to create a new ethics and transform the values that structure our institutions is in teaching. This is not to say that such transformation will be easy. Those of us teaching in the US are working within a system that instills these notions of competition and individual achievement earlier and earlier, of course, as students come to us from elementary and secondary institutions increasingly structured around testing. Those students aren't competing directly against one another in the moment of testing, but they are nonetheless being inculcated into at least two of competitive thinking's underpinnings: the responsibility of the individual for demonstrating mastery, and the significant consequences of being wrong.

+

+

+# wrong

+

+Note: And perhaps it's here that we see the origins of my students' tendency to freeze when asked to restate the argument of something they'd read: their answer might have been wrong. As Kathryn Schulz has explored, all of us will go to extraordinary lengths to avoid being wrong, or acknowledging our wrongness. But of course there is no real thinking without the possibility -- indeed, somewhere along the line, the inevitability -- of being wrong. Without being willing to be wrong, we can't hypothesize, we can't experiment, we can't create. We can't imagine new possibilities. We can't dream. But we are hard-wired not to admit the possibility that we might be wrong.

+

+

+# you're wrong

+

+Note: And one key method by which we attempt to avoid the possibility of being wrong -- and again, by "we" here, I mean both to point to academics in particular and to humans living at the end of the second decade of the twenty-first century in general -- again, one key method by which we attempt to avoid the possibility of being wrong is by demonstrating the inherent wrongness in everyone else's ideas. In the academy, and perhaps especially in the humanities and social sciences, this takes the form of critique: if I can demonstrate what's wrong with your ideas, it must mean that my ideas are better.

+

+

+# critique

+

+Note: This is the upshot of our misapplication of _They Say, I Say_, and it's what leads to the situation I faced in my graduate seminar: we have armed our students with all the most important tools of critique. They are ready to unpack and dismantle. They are well-trained, that is to say, in playing what Peter Elbow once referred to as the doubting game, in which they focus on the parts of an idea that could be wrong and what it might mean if they were. But they have -- and if we're willing to be honest with ourselves, we all have -- a tendency to skip the half of the game that's supposed to come first: the believing game, in which we focus on what it might mean if the idea were right. Our reading of _They Say, I Say_, in other words, encourages us to dismiss what "they say" as quickly as possible, in order to get on to the more crucial "I say," the part for which we will actually get credit.

+

+

+# critical thinking

+

+Note: I want to be clear here: there is a LOT of what "they say" that in fact should be pushed back against. There's a lot out there worth doubting. I'm not asking us not to disagree, not to push new ideas forward, not to think critically. I am, however, hoping that we might find ways to remember that critical thinking requires deep understanding and even generosity as a prerequisite. And perhaps nowhere are the generous underpinnings of critical thinking more important than in international education: as students are brought into contact with cultures that are new to them, they need to be equipped with the kind of tools that will allow them to recognize what they don't know, and allow them to be open to learning.

+

+

+# generosity

+

+Note: So in that spirit, what I want to ask today is what we and our students might gain from slowing the process down, from emphasizing the believing game before leaping to the doubting game, from lingering a bit longer in the "they say." We might, just as a start, find that we all become better listeners. We might open up new ground for mutual understanding, even with those from whom we are most different and with whom we most disagree.

+

+

+# we say

+

+Note: And we might find ourselves moving less from "they say" to "I say" than instead to "we say," thinking additively and collaboratively about what we might build together rather than understanding our own ideas to require vanquishing everyone else's. A more generous model of education might emerge, one based on building something collective rather than tearing down our predecessors in order to promote our own ideas. This generous education might help us frame ways of thinking that focus on how our institutions might serve as means of fostering community rather than providing individual benefit.

+

+

+# generous thinking

+

+Note: And this model of generous thinking is key to the future of the university: we have to find our way back to an understanding of the university's work as grounded in service to a broadly construed public, and that requires all of us -- faculty, students, staff, administrators, trustees -- reframing the good that higher education provides as a social good, a collective and communal good, rather than a personal, private, individual one.

+

+

+# generous assessment

+

+Note: Of course, if we are really going to effect this transformation -- what amounts to a paradigm shift in thinking about the values that underwrite higher education -- we're going to have to think differently about how we measure our success as well. About what success means in the first place. If we're going to move away from the every-tub-on-its-own-bottom, hyper individualistic, competitive mode of achievement, in which all outcomes are understood to be individual and are therefore assessed at that level, and instead foster more collective goals, we're going to need to think carefully about what we're assessing and why. How might we instead focus our modes of assessment at all levels, and the rewards that follow, on collaboration, on process?

+

+

+# us

+

+Note: If we're going to bring this mode of generous thinking, of generous argument, of generous assessment to bear on our classrooms, of course, we'd be well served by bringing it to bear on our work together first. We need to think seriously about how all of the processes that structure professional lives within the academy -- not least our processes of hiring, of retention, of tenure and promotion -- might be transformed in order to instantiate the values we want to bring to the work we do, rather than fostering the culture of competition, of invidious distinction, that colors all of the ways that we work today, and the environment within which our students learn.

+

+

+# critique

+

+Note: One cautionary note, however: I do not mean this emphasis on generosity, on a supportive engagement with the work that has gone before us, to be used as a means of defusing the important work that critique actually does in helping make ideas better. In the early days of working on _Generous Thinking_, I gave an invited talk in which I tested out some of its core ideas. In the question-and-answer period that followed, one commenter pointed out what he saw as a canny move on my part in talking about generosity: no one wanted to be seen as an ungenerous jerk in disagreeing with me. It was a funny moment, but it gave me real pause; I did not at all intend to use generosity as a shield with which to fend off the possibility of critique. Generosity, in fact, requires remaining open to criticism -- in fact, it requires recognizing the generous purposes that critique can serve. So in pressing for more generous modes of education and more generous modes of assessment, I do not mean to impose a regime that is all rainbows and unicorns on us. Instead, what I'm hoping to ask is how we might all benefit from thinking *with* rather than *against* one another, *with* rather than *against* the arguments of our predecessors, and *with* rather than *against* our students in developing the knowledge that might make all of us better contributors to the social good.

+

+

+# questions

+

+Note: I've asked a lot of questions about what we might do and how it might work, and I'm not sure how many answers I have for them. In part, that's by design: the problems facing the university today are larger and more complicated than can be solved by any one mind working alone. They're going to require all of us, thinking together, building one one another's ideas, in order to create something new. And so I'm going to stop here, in the hopes that we might use the rest of this time to move from what *I say* to what *we say.* I'd love to hear your thoughts about how we might encourage more generous forms of education, and how we might use that generosity to encourage new ways of being in the world.

+

+

+## thank you

+---

+##### Kathleen Fitzpatrick // @kfitz // kfitz@msu.edu

+

+Note: Many thanks.

+

diff --git a/alma.html b/alma.html

new file mode 100644

index 00000000..dd4aec39

--- /dev/null

+++ b/alma.html

@@ -0,0 +1,58 @@

+

+

+

+

+

+

+ Generous Thinking

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

diff --git a/alma.md b/alma.md

new file mode 100644

index 00000000..f5241c62

--- /dev/null

+++ b/alma.md

@@ -0,0 +1,171 @@

+## Generous Thinking

+---

+### and the Future of the Liberal Arts

+---

+

+##### Kathleen Fitzpatrick // @kfitz // kfitz@msu.edu

+

+Note: I want to start by thanking President Abernathy for inviting me to spend the day with you here. This talk draws heavily on various parts of my book, _Generous Thinking_, which was published in February by Johns Hopkins. The overall argument of the project is that the future of higher education depends on institutions, and those of us who are part of them, successfully building engaged, trusting relationships with the publics that the our institutions are intended to serve. This is perhaps especially obvious for public colleges and universities like my own, but I believe that it is no less true of private institutions, including liberal arts colleges, which depend on various kinds of public support for their success.

+

+

+

+##### http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank

+

+Note: That we need to place some emphasis on building these relationships between our institutions and our publics can be seen in the results of an increasing number of reports and studies such as this one, released in 2017 by the Pew Research Center. The report documents a precipitous decline in the esteem colleges and universities are held in in the United States, primarily on the political right. It's not a surprise; we've seen this kind of shift in public opinion taking root for some time. Typically our response to this kind of report, however, has been to decry the rampant anti-intellectualism in contemporary culture and to turn inward, to spend more time talking internally with those who understand what we do. In that reaction, however, we run the risk of deepening the divide, allowing those who _want_ us to fade into irrelevance to say "see? They're out of touch. Who needs them anyway?" It's important for us to remember that this shift in public opinion didn't just happen by itself; it was made to happen as part of a program of discrediting and privatizing public services across the nation.

+

+

+

+##### http://chronicle.com

+

+Note: However: from time to time we are confronted with undeniable evidence that many of our institutions -- even those institutions that most profess their commitment to public service -- have utterly betrayed the trust that public has placed in them. Which is to say that the problem is not just that the public fails to understand the importance of what we do; it's also that we have, in many ways, failed: failed to make that importance clear, failed to protect our communities both on-campus and off, failed to build institutions that are genuinely, structurally capable of living out the values they profess. So a large part of what I'm after in _Generous Thinking_ is to press for new ways of understanding our institutions _as_ communities, as well as _in interaction with_ communities, asking us to take a closer look at the ways that we communicate both with one another and with a range of broader publics about and around our work. And some focused thinking about that mode of public engagement is in order, I would suggest, because our institutions are facing a panoply of crises that we cannot resolve on our own.

+

+

+# crisis

+

+Note: These crises don't always give the impression of approaching the kind or degree of the highly volatile political, economic, and environmental situation we are currently living through. And yet the decline in public support for higher education is of a piece with these other crises, part of a series of national and international transformations in assumptions about the responsibility of governments for the public good -- the very notion, in fact, that there _can be_ such a thing as the public good -- and the consequences of those transformations are indeed life or death in many cases. So while my argument about the importance of generosity for the future of the university might appear self-indulgent, a head-in-the-sand retreat into philosophizing and a refusal of real political action, I hope, in the book, to have put together a case for why this is not so -- why, in fact, the particular modes of generous thinking that I am asking us to undertake within and around our institutions of higher education have the potential to help us navigate the present crises. Many of our fields, after all, are already focused on pressing public issues, and many of us are already working in publicly engaged ways. We need to generalize that engagement, and to think about the ways that it might, if permitted, transform the institution and the ways that we all work within it. That is to say, the best of what the university has to offer -- what matters most -- may lie less in its power to advance knowledge in any of its particular fields than in our ability to be a model and a support for generous thinking as a way of being in and with the world.

+

+

+# "we"

+

+Note: But first: who is this "we" I keep referring to, what is it that we do, and why does it matter? Much of what I have written focuses on the university's permanent faculty, partially because that faculty is my community of practice and partially because of the extent to which the work done by the faculty is higher education: research and teaching are the primary purposes and visible outputs of our institutions. Moreover, the principles of shared governance under which we operate -- at least in theory -- suggest that tenured and tenure-track faculty members have a significant responsibility for shaping the future of the university. But it's important to be careful in deploying this "we"; as Helen Small has pointed out,

+

+

+> "The first person plural is the regularly preferred point of view for much writing about the academic profession for the academic profession. It is a rhetorical sleight of hand by which the concerns of the profession can be made to seem entirely congruent with those of the democratic polity as a whole."

-- Helen Small

+

+Note: "The first person plural is... a rhetorical sleight of hand by which the concerns of the profession can be made to seem entirely congruent with those of the democratic polity as a whole." While I hope that my argument has something important to say to folks who work on university campuses but are not faculty, or who do not work on university campuses at all, that connection can't be assumed. It would be great if we could make it possible for the "we" I focus on here to refer to all of us, on campus and off, who want to strengthen both our systems of higher education and our ways of engaging with one another in order to help us all build stronger communities, to ensure that all of us count -- but that's part of the work ahead.

+

+

+# "them"

+

+Note: So it's important to be careful about how we define "us," precisely because every "us" implies a "them," and the ways we define and conceive of that "them" points to one of the primary problems of the contemporary university, and especially public universities in the US. These institutions were founded explicitly in service to the people of their states or regions or communities, and thus those publics should be understood as part of "us." And yet, the borders of the campus have done more than define a space; they determine a sense of belonging as well, transforming everything off-campus into "them," a generalized other. Granted, sometimes "they" are imagined to be the audience for our performances, a passive group that benefits from and takes in information we provide. But what might it mean if we understood ourselves, and our institutions, as embedded in and responsible to the complex collection of communities by which we are surrounded? How might we develop a richer sense not just of "them" but of the "us" that we together form?

+

+

+# "community"

+

+Note: We talk a lot, after all, about community on campus, both about community engagement and about the institution itself as a community, but we don't often talk about what it is we mean when we invoke the concept. Miranda Joseph explores the ways in which "community" gets mythologized, romanticized, and so comes to serve what she calls a supplementary role with respect to capitalism, filling its gaps and smoothing over its flaws in ways that permit it to function without real opposition. Additionally, "community" in the singular -- "the community" -- runs the risk of becoming a disciplinary force, a declaration of groupness that is designed to produce the "us" that inevitably suggests a "them."

+

+

+# solidarity

+

+Note: If we understand community instead as multiple and diverse, as shifting entities that serve strategic purposes, we might be able to embrace community not as a declaration but as an activity, a practice of solidarity, a process of coalition-building. It is a way of rethinking who counts, of adding others to our numbers, and adding ourselves to theirs. This call for solidarity between the university and the communities outside its walls is part of higher education's recent history, the subject of the student-led calls for institutional change that spanned the 1960s and 1970s. As Roderick Ferguson has detailed, however, those calls were met with deep resistance, not only within the institution but in the governmental and corporate environment that oversaw it, leading to the political shifts whose apotheosis we are living today. In reaction, our institutions, rather than tearing down their walls, instead turned inward, become self-protective, looked away from the possibility of building solidarity with the publics that the university was meant to serve. Community in this strategic sense is and has been the university's weakness, when it should have been its strength. If we are to save our institutions from the relentless economic and political forces that today threaten to undo them, we must begin to understand our campus as a site where new kinds of communities, and new kinds of solidarities, can and must be built.

+

+

+# liberal education

+

+Note: However, in building those relationships, we have to contend with the fact that what faculty members actually _do_ on our campuses is often a mystery, and indeed a site of profound misunderstanding, for people outside the academic profession, and even at times for one another. One of the key areas of misunderstanding, and one that most needs opening up, is the fundamental purpose of higher education. Public figures such as politicians increasingly discuss colleges and universities as sites of workforce preparation, making it seem as if the provision of career-enhancing credentials were the sole purpose for which our institutions exist, and as if everything else they do that does not lead directly to economic growth were a misappropriation of funds. Those of us who work on campus, by and large, understand our institutions not as credentialing agencies but as sites of broad-based education: a "liberal" education in the original sense of the term. Of course the very term "liberal education," so natural to those of us steeped in it, has itself become profoundly politicized, as if the liberal aspect of higher education were not its breadth but its ideological bent. So we see, for instance, the state of Colorado stripping the term out of official university documents. But even where the concept of liberal education isn't imagined to be a cover for some revolution we're fomenting on campus, there's a widespread misconception about it that's almost worse: it is a mode of education in which we waste taxpayer resources by developing, disseminating, and filling our students' heads with useless knowledge that will not lead to a productive career path.

+

+

+# humanities

+

+Note: And nowhere is this misconception more focused than on the humanities. The portrait I'm about to sketch of the humanities today could be extended to many other areas within the curriculum -- for example, the sciences' focus on "basic science," or science without direct industry applicability, is often imagined to be just as frivolous. But the humanities -- the study of literature, history, art, philosophy, and other forms of culture -- are in certain ways both the core and the limit case of the liberal arts. The humanities cultivate an inquisitive mindset, they teach key skills of reading and interpretation, and they focus on writing in ways that can prepare a student to learn absolutely anything else over the course of their lives -- and yet they are the fields around which no end of hilarious jokes about what a student might actually do with that degree have been constructed. (The answer, of course: absolutely anything. As a recent report from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences makes clear, not only do humanities majors wind up gainfully employed, but they also wind up happy in their choices. But I digress.) The key thing to note is that the humanities serve as a bellwether of sorts: what has been happening to them is happening to higher education in general, if a little more slowly. So while I'm focused here on the kinds of arguments that are being made about the humanities in our culture today, it doesn't take too much of a stretch to imagine them being made about sociology, or about physics, or about any other field on campus that isn't named after a specific, well-paying career.

+

+

+# marginalization

+

+Note: The humanities, in any case, have long been lauded as providing students with a rich set of interpretive, critical, and ethical skills with which they can engage the world around them. These skills are increasingly necessary in today's hypermediated, globalized, conflict-filled world -- and yet many humanities departments find themselves increasingly marginalized within their own institutions. This marginalization is related, if not directly attributable, to the degree to which students, parents, administrators, trustees, politicians, the media, and the public at large have been led in a self-reinforcing cycle to believe that the skills these fields provide are useless in the current economic environment. Someone particularly visible makes a publicly disparaging remark about all those English majors working at Starbucks; commentators reinforce the sense that humanities majors are worth less than pre-professional degrees; parents strongly encourage their students to turn toward pragmatic fields that seem somehow to describe a job; administrators note a decline in humanities majors and cut budgets and positions; the jobs crisis for humanities PhDs worsens; someone particularly visible makes a publicly disparaging remark about what all those adjuncts were planning on doing with that humanities PhD anyhow; and the whole thing intensifies. In many institutions, this draining away of majors and faculty and resources has reduced the humanities to a means of ensuring that students studying to become engineers and bankers are reminded of the human ends of their work. This is not a terrible thing in and of itself, but it is not a sufficient ground on which humanities fields can do their best work for the institution, or for the world.

+

+

+# spreading

+

+Note: And while this kind of cyclical crisis has not manifested to anything like the same extent in the sciences, there are early indications that it may be spreading in that direction. Where once the world at large seemed mostly to understand that scientific research, and the kinds of study that support it, are crucial to the general advancement of knowledge, recent shifts in funder policies and priorities suggest a growing scrutiny of that work's economic rather than educational impact, as well as a growing restriction on research areas that have been heavily politicized. The humanities, again, may well be the canary in the higher education coal mine, and for that reason, it's crucial that we pay close attention to what's happened in those fields, and particularly to the things that haven't worked as the humanities have attempted to remedy the situation.

+

+

+# defense

+

+Note: One of the key things that hasn't worked is the impassioned plea on behalf of humanities fields: a welter of defenses of the humanities from both inside and outside the academy have been published in recent years, each of which has seemed slightly more defensive than the last, and none of which have had the desired impact. Calls to save the humanities issued by public figures have frequently left scholars annoyed, as they often begin with a somewhat retrograde sense of what we do and why, and thus frequently give the sense of trying to save our fields from us. (One might see, for instance, a column published in 2016 by the former chairman of the NEH, Bruce Cole, entitled "What's Wrong with the Humanities?", which begins memorably:

+

+

+> "Let's face it: Too many humanities scholars are alienating students and the public with their opacity, triviality, and irrelevance."

-- Bruce Cole

+

+Note: "Let's face it: Too many humanities scholars are alienating students and the public with their opacity, triviality, and irrelevance.") But perhaps even worse is the degree to which humanities professors themselves -- those one would think best positioned to make the case -- have failed to find traction with their arguments. As the unsuccessful defenses proliferate, the public view of the humanities becomes all the worse,

+

+

+> "Whatever things the humanities do well, it is beginning to look as if promoting themselves is not among them."

-- Simon During

+

+Note: leading Simon During to grumble that "Whatever things the humanities do well, it is beginning to look as if promoting themselves is not among them." And maybe we like it that way, as we are often those who take issue with our own defenses, bitterly disagreeing as we frequently do about the purposes and practices of our fields.

+

+

+# definition

+

+Note: Perhaps this is a good moment for us to stop and consider what it is that the humanities do do well, what the humanities are for. I will start with a basic definition of the humanities as a cluster of fields that focus on the careful study and analysis of cultures and their many modes of thought and forms of representation -- writing, music, art, media, and so on -- as they have developed and moved through time and across geographical boundaries, growing out of and adding to our senses of who we are as individuals, as groups, and as nations. The humanities are interested, then, in the ways that representations work, in the relationships between representations and social structures, in all the ways that human ideas and their expression shape and are shaped by human culture. In this definition we might begin to see the possibility that studying literature or history or art or film or philosophy might not be solely about the object itself, but instead about a way of engaging with the world: in the process we develop the ability to read and interpret what we see and hear, the insight to understand the multiple layers of what is being communicated and why, and the capacity to put together for ourselves an appropriate, thoughtful contribution to our culture.

+

+

+# disagreement

+

+Note: Now, the first thing to note about this definition is that I am certain that many humanities scholars who hear it will disagree with it -- they will have nuances and correctives to offer -- and it is important to understand that this disagreement does not necessarily mean that my definition is wrong. Nor, however, do I mean to suggest that the nuances and correctives presented would be wrong. Rather, that form of disagreement is at the heart of how we do what we do: we hear one another's interpretations (of texts, of performances, of historical events) and we push back against them. We advance the work in our field through disagreement and revision. This agonistic approach, however, is both a strength of the humanities -- and by extension of the university in general -- and its Achilles' heel, a thought to which I'll return shortly.

+

+

+# sermonizing

+

+Note: For the moment, though, back to Simon During and his sense that the humanities are terrible at self-promotion. During's complaint, levied at the essays included in Peter Brooks and Hilary Jewitt's volume, _The Humanities and Public Life_, is largely that, in the act of self-defense, humanities scholars leave behind doing what they do and instead turn to "sermonizing" (his word) about the value of what they do. He argues that part of the problem is the assumption that the humanities as we practice them ought to have a public life in the first place. He winds up suggesting that we should continue to ensure that there is sufficient state support for the humanities so that students who do not already occupy a position of financial comfort can study our fields, but that we should not stretch beyond that point by arguing for the public importance of studying the humanities, because that importance is primarily, overwhelmingly, private.

+

+

+# privatization

+

+Note: This sense that education in the humanities is of primarily private value is increasingly in today's popular discourse extended to higher education in general: the purpose, we are told, of a college degree is some form of personal enrichment, whether financial or otherwise, rather than a social good. This privatization of higher education's benefits -- part of the general privatization that Chris Newfield has referred to as the academy's "great mistake" -- has been accompanied by a related shift in its costs from the state to individual families and students, resulting in the downward spiral in funding and other forms of public support in which our institutions and our fields are caught, as well as the astronomically increasing debt load faced by students and their families. As long as a university education is assumed to have a predominantly personal rather than social benefit, it will be argued that making such an education possible is a private rather than a public responsibility. And that mindset will of necessity lead to the devaluation of fields whose benefits are less immediately tangible, less material, less individual. If we are to correct course, if we are to restore public support for our institutions and our fields, we must find ways to make clear the public goals that our fields have, and the public good that our institutions serve.

+

+

+# public good

+

+Note: But what is that public good? We don't always do a terribly good job of articulating these things, of describing what we do and arguing on behalf of the values that sustain our work. That may be in part because it's hard to express our values without recourse to what feel to us like politically regressive, universalizing master narratives about the nature of the good that have long been used as means of solidifying and perpetuating the social order, with all its injustices and exclusions. And so instead of stating clearly and passionately the ethics and values and goals that we bring to our work, we critique. We protect ourselves with what Lisa Ruddick has described as "the game of academic cool": in order to avoid appearing naïve -- or worse, complicit -- we complicate; we argue; we read against the grain.

+

+

+# critique

+

+Note: One of the things that happens when we engage in this mode of critique is that we get accused of having primarily ideological ends; this is how our universities come to be accused of "brainwashing" their students, filling their heads with leftist rejections of the basic goodness of the dominant western culture. On campus, of course, we know that's not true; our classes in American history and in English literature may strive to teach the full range of that history and that literature, but western culture is far from being marginalized in the curriculum. And, in fact, even our most critical reading practices turn out to be perfectly compatible with the contemporary political landscape. In fact, in the larger project, I argue that our critiques of contemporary culture surface not just despite but because of the conservative-leaning systems and structures in which the university as a whole, and each of us as a result, is mired. Our tendency to read against the grain is part of our makeup precisely because of the ways that we are ourselves subject to politics rather than being able to stand outside and neutrally analyze the political. The politics we are subject to -- one that structures all institutions in the contemporary United States, and perhaps especially universities -- makes inevitable the critical, the negative, the rejection of everything that has gone before. It is a politics structured around competition, and what historian Winfried Fluck has referred to as the race for individual distinction.

+

+

+# individualism

+

+Note: However much we might reject individualism as part and parcel of the neoliberal mainstream, our working lives -- on campus and off -- are overdetermined by it. The entire academic enterprise serves to cultivate individualism, in fact. From college admissions through the entirety of our careers, those of us on campus are subject to selection. These processes present themselves as meritocratic: there are some metrics for quality against which we are measured, and the best -- whatever that might mean in a given context -- are rewarded. In actual practice, however, our metrics are never neutral, and what we are measured against is far more often than not one another. We are in constant competition: for positions, for resources, for acclaim. And the drive to compete that this mode of being instills in us can't ever be fully contained by these specific processes; it bleeds out into all areas of the ways we work, even when we're working together. Hence the danger of our agonistic modes of work: too often, that agon is turned on one another, discrediting competing theories rather than building on one another's work.

+

+

+# competition

+

+Note: This competitive individualism contradicts -- and in fact undermines -- all of the most important communal aspects of life within our institutions of higher education. Our principles of shared governance, for instance, are built on the notion that universities best operate as collectives, in which all members contribute to their direction and functioning, but in actual practice, our all-too-clear understanding that service to the institution will not count when faculty are evaluated and ranked for salary increases and promotions encourages us to avoid that labor, to reserve our time and energy for those aspects of our work that will enable our individual achievement. The results are not good for any of us: faculty disengage from their colleagues, from the functioning of the institution and the shared purposes that it serves, while university governance becomes increasingly managed by administrators, ostensibly freeing the faculty up to focus on the competitive work that will allow us as individuals and our universities as institutions to climb the rankings. This is no way to run a collective. It's also no way to build solidarity among academic units, or across categories of academic employment, or between the academy and the communities with which it engages.

+

+

+# the point

+

+Note: And perhaps that's the point. Perhaps we are locked into this endless competition with one another in order to keep us distracted from the work that we might do if we were truly joined together. The requirement that we continually compare ourselves with one another, that we take on only the work that will lead to our own individual achievement, is inseparable from the privatization that Newfield describes as the political unconscious of the contemporary university. Competition and the race for individual distinction structure the growing conviction that not only the benefits of higher education but also all of our categories of success can only ever be personal, private, individual rather than social.

+

+

+# so

+

+Note: So how do we step off of this treadmill? How do we begin to insist upon living our academic lives another way? How do we return to the collective, the social, the communal potential that higher education should enable?

+

+

+# generous thinking

+