## Scholarly Communication

### DH865 -- Spring 2018

[Kathleen Fitzpatrick](http://kfitz.msu.domains) // [@kfitz](http://twitter.com/kfitz) // [kfitz@msu.edu](mailto:kfitz@msu.edu)

Note: This lecture is going to walk through a bunch of work that I've done over the course of the last decade-plus and the arguments that lead up to my current projects, which focus in different ways on the future of scholarly communication. I hope that we'll be able to spend some time afterward with any questions that you may have about the ways we write and publish today and how your own work might be affected. Most of my thinking is pretty inescapably shaped by my own fields, English and media studies, which are largely book-oriented, but I think there are some relationships that can be drawn to the other forms of scholarly communication that are dominant in other areas of the academy today.

## overview

1. the first book, aka the crisis

2. blogs and networks

3. the second book

4. peer review

5. scholarly communities

## 1. the first book,

## aka the crisis

Note: So while much of what I'm talking about today is focused on the present and future of scholarly communication, it starts with the past, in no small part because certain aspects of the ways that humanities scholars in the US have traditionally worked are rapidly becoming obsolete. By this, however, I don’t mean to say that we are facing the imminent “death” of the book, for instance, only that certain aspects of our reliance on the book as a primary mode of scholarly communication aren’t serving us as well as they once did. In fact, the argument that I made in my first book,

## the anxiety of obsolescence

Note: The Anxiety of Obsolescence: The American Novel in the Age of Television, was precisely that the so-called

## “death of the novel”

Note: “death of the novel” much bemoaned in the late twentieth century wasn’t at all based in material fact, but was instead an ideological claim designed to ensure the novel’s continuance. This continues to be true: neither the novel nor the book more broadly, nor even print in general are in any sense dying forms, but claims of this demise are often used as a means of creating what I like to think of as a kind of

## “cultural wildlife preserve”

Note: cultural wildlife preserve, a protected space within which a form that is apparently under threat from predatory forms of newer media can flourish. I bring my first book project up in no small part because of what happened once I’d finished that manuscript. Naively, I’d assumed that publishing a book that makes the argument that the book isn’t dead wouldn’t be that hard, that somebody might have an interest in getting that argument into print. What I hadn’t counted on, though, was the effect that

## dot-com crash

Note: the first dot-com crash was having on university presses. It took me nearly a year to find a press willing to consider the project, as press after press told me how much they liked it, but that they just couldn’t afford to publish it. Finally, though, I found a willing press, and in December 2003, after the manuscript had been under review for ten months, I received an email message from the editor. The news was not good: the press was declining to publish the book. The note, which was as encouraging as a rejection can ever be, stressed that in so far as fault could be attributed, it lay not with the manuscript but with the climate; the press had received two enthusiastically positive readers’ reports, and the editor was supportive of the project. The marketing department, however, overruled him on the editorial board, declaring that the book posed

> “too much financial risk… to pursue in the current economy.”

— the marketing guys

Note: “too much financial risk… to pursue in the current economy.”

This particular cause for rejection prompted two immediate responses, one of which was most clearly articulated by my mother, who said

> “They were planning on making money off of your book?”

— my mom

Note: “they were planning on making money off of your book?” The fact is, they were — not much, perhaps, but that the press involved needed the book to make money, at least enough to return its costs, and that it doubted it would, highlights one of the most significant problems facing academic publishing today:

## insupportable economic model

Note: an insupportable economic model. To backtrack for a second: university presses in the United States were founded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a means of distributing the work being produced by university-based scholars, precisely because _there was no market_ for that work, and so commercial publishers refused to take it on. In order to get scholars’ work into circulation, universities had to take on the responsibility for reproducing and circulating it, often giving it away for free to other institutions’ libraries, in exchange for similar work being produced at those institutions. And yet gradually, over the course of the first half of the 20th century, university presses professionalized, becoming revenue centers on their campuses rather than service organizations. As a result, market values all but inevitably came to be applied to the circulation of scholarship — and almost from that moment, the discussion of

## “crisis”

Note: the “crisis in scholarly publishing” was born.

Though these problems have been building for a long time, things suddenly got much, much worse after the dot-com bubble burst in 2000. During this dramatic turn in the stock market, when many US university budgets took a nosedive (a situation that 2008 made to seem like mere foreshadowing), among the academic units whose budgets took the hardest hits were

## university presses and university libraries

Note: university presses and university libraries. And the cuts in funding for libraries represented a further budget cut for presses, as numerous libraries, already straining under

## rising cost of journals

Note: the exponentially rising costs of journals, especially in the sciences, managed the cutbacks by reducing the number of books they purchased. The result for many university library users was perhaps only a slightly longer wait to obtain any book they needed, as libraries increasingly turned to collection-sharing arrangements, but the result for presses was devastating. For a university press of the caliber of, say, Harvard’s, the expectation for decades was that they could count on every library in the University of California system buying a copy of each title they published. After 2001, however, the rule increasingly became such that one library in the system would buy that title - and today even that’s not a certainty, given systems of demand-driven acquisition being implemented at many libraries. This has happened with every system around the country, such that by 2004, sales of monographs to libraries had already fallen to less than

## one-third

Note: one-third of what they had been in the previous decade — and again, that was in 2004, a full fourteen years of crisis ago. So library cutbacks resulted in vastly reduced sales for university presses, at precisely the moment when severe cutbacks in the percentage of university press budgets

## subsidies

Note: provided through institutional subsidies have made those presses dependent on income from sales for their survival. (The average university press receives well under 10% of its annual budget from its institution, and must make up the rest with revenue from sales.) It’s for this reason, among others, that I have argued that the financial model under which university press publishing operates is simply not sustainable into the future. A foretaste of a likely future has been visible for a while now, as a number of presses have been shut down by their institutions -- the University of Kentucky's press is the most recent to be threatened with being closed -- and nearly all of those that have survived

## reduced number of titles published

Note: have been required to reduce the number of titles that they publish each year, especially in smaller fields, and as

## marketing

Note: marketing concerns have come at times, of necessity, to compete with scholarly merit in making publication decisions.

In my case, things turned out fine; the book got picked up (if only well over a year later) by a smaller press, one with more modest sales expectations, and the book managed to exceed those expectations - as well, ironically, as the requirements of the first press. But despite the fact that The Anxiety of Obsolescence was, finally, successfully published, my experience of the crisis in academic publishing led me to begin rethinking my earlier argument that the book wasn’t an endangered species. Perhaps there is a particular form of book —

## the academic book

Note: the academic book — that is indeed threatened with a kind of obsolescence. Even so, this is not to say that the academic book is dead. These books are still published, after all, if not exactly in the numbers they might need to be in order to satisfy all our hiring and tenure requirements, and they still sell, if not exactly in the numbers required to support the presses that put them out. The academic book is, however, in a curious state, one that might usefully complicate conventional associations of obsolescence with the “death” of this or that cultural form, for while the academic book is

## no longer viable, but still required

Note: no longer viable as a primary means of scholarly communication, it is still required in many fields in the US in order to obtain tenure. If anything, the academic book isn’t dead; it's kind of

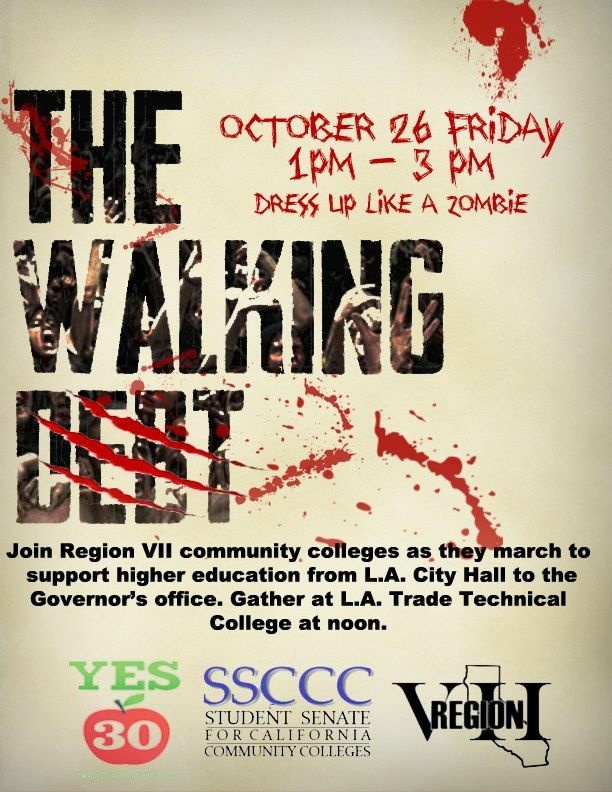

## undead

Note: undead, exercising power over the ways we work without really, truly, being alive. There's a sort of zombie logic to the academic book, which begins to make a particular kind of sense if you consider the extensive scholarship in media studies on the figure of the zombie,

Note: which is often understood to act as a stand-in for the narcotized subject of capitalism, particularly at those moments when capitalism’s contradictions become most apparent. If there is a relationship between the zombie and the subject of late capital, the cultural anxiety that figure marks has been, of late, off the charts.

Note: Zombies are everywhere for a reason, and not least within the academy, as we not only find our ways of communicating increasingly threatened with a sort of death-in-life,

## death-in-livelihood

Note: but also find our livelihoods themselves decreasingly lively, as the liberal arts are overtaken by the study of ostensibly more pragmatic fields, as a growing culture of assessment requires us to spend more time accounting for our work and less actually doing the work itself, as tenure-track faculty lines in US institutions are rapidly being replaced with more contingent forms of labor, and as too many newly-minted PhDs are finding themselves without the job opportunities they need to survive.

## really?

Note: Just to be clear: I am not suggesting that the future survival of the academy requires us to put academic publishing safely in its grave. But I'm not being wholly facetious either, as I do want to indicate that certain aspects of scholarly communication today are neither quite as alive as we'd like them to be, nor quite as dead as might be most convenient. Because, honestly, we'd probably do just fine if the book were actually dead; we'd turn our attention to ensuring that new forms of scholarly communication were as powerful and vibrant as they could be, rather than continuing to fetishize one particular shape.

## 2. blogs and networks

Note: For instance, we might more fully explore the potentials presented for scholarship by blogs and other personally-hosted or networked writing platforms. I suggest this in no small part because while I was finishing the manuscript for my first book, I found myself getting antsy. No one was reading my work, and I really wanted to get some thoughts in front of readers. And in a fit of procrastination one day in 2002, I was googling some old friends from grad school, and discovered that one of them had an amazing blog. It was smart, it was funny, and I knew that people were reading it because they responded to his posts in the comments.

Note: So I started a blog. Though it didn't look so much like this at the time.

Note: It looked more like this. Not fancy at all, and somewhat off the official pathway that was laid out for my scholarly work, but it allowed me to

1. Write more frequently

2. Get faster responses

3. Build a community

## conversations

Note: And that community was key. Some of what the blog produced for me looked a lot like conversations with friends; in fact, some of my best friends today were folks that I stumbled across in blog-land, including the Wordherders, a blogging collective run by an English grad student out of the University of Maryland. Conversations with that cluster of folks were key to most of the work that I did in the ensuing years. (Incidentally, that grad student was Jason Rhody, who went on to be one of the founding program officers in the Office of Digital Humanities at the NEH.)

## ephemerality

Note: One of the ironies of the impact that blogging had on the development of my career, especially given that I was writing about obsolescence, is the blog's almost perfectly ephemeral form: each post scrolls down the front page and off into the archives — and yet, the apparent ephemerality of the blog post also has a surprising

## durability

Note: durability, thanks the technologies of searching, filtering, and archiving that have developed across the web, as well as to the networked conversations that keep the archives in play. Blogs do die, often when their authors stop posting, sometimes when their authors fail to renew their domain names. But even when apparently dead, a blog persists, in archives and caches, and continues to draw readers in through old links and search engines. A form of obsolescence may be engineered into a blog’s architecture, but this ephemerality is misleading; our interactions with blogs keep them alive long after they’ve apparently died.

## obsolescence

Note: So I found myself thinking a lot about the differences between the apparent ephemerality of the blog and the possible obsolescence of the academic book, and what that meant. It's not so much that the book as a material form is becoming obsolete, after all, as it is that something in the ways we produce and disseminate the content that circulates in book form that is ceasing to function as well as it should.

## institutional

Note: It's an institutional problem, in other words. I mentioned earlier that the message I’d received from that press, declining my book on financial grounds, produced two immediate responses. The first was my mother’s bewildered disbelief; the second came from my Wordherder friend Matt Kirschenbaum, who left a comment on a blog post of mine saying that he couldn't understand why I couldn’t simply take the manuscript and the two positive readers’ reports and put the whole thing online — voilà: peer-reviewed publication — where it would likely garner a readership both wider and larger than the same manuscript in print would.

Note: “In fact I completely understand why that’s not realistic,” he went on to say, “and I’m not seriously advocating it. Nor am I suggesting that we all become our own online publishers, at least not unless that’s part of a continuum of different options. But the point is, the system’s broken and it’s time we got busy fixing it. What ought to count is peer review and scholarly merit, not the physical form in which the text is ultimately delivered.”

This exchange with Matt, and a number of other conversations that I had on the blog, persuaded me to stop thinking about

## scholarly publishing

Note: scholarly publishing as a system that would simply bring my work into being, and instead approach it as the object of that work, thinking seriously about both the institutional models and the material forms through which scholarship might best circulate. So I started noodling online about the possibility of founding an all-electronic scholarly press,

Note: including writing a guest post on The Valve, then a widely-read group blog in literary studies. It seemed clear to me that we couldn't just change the technologies through which we publish and allow everything else to stay the same; in fact, we needed a deep rethinking of the processes through which the academy tenures its faculty, of the ways those faculty do their work, the ways they communicate that work, and the ways that work is read both inside and outside the academy. Those changes had to be both social and institutional. Creating the possibility for such change became the focus of a cascading series of projects that I began work on then, all of which were aimed at creating the kinds of change I think necessary for the survival of scholarly communication in the humanities into the twenty-first century.

## mediacommons

Note: The first of these was MediaCommons, an early digital scholarly publishing network focused on media studies, which my colleague Avi Santo and I co-founded with support from the Institute for the Future of the Book, the NEH Office of Digital Humanities, and the NYU Digital Library Technology Services group.

Note: MediaCommons has worked over the last ten years to become a space in which the multiplicity of conversations in and about media studies taking place online can be brought together, through a range of projects that experiment with the form, the weight, and the time signature of scholarly communication.

Note: The longest-running of these projects is In Media Res, which asks five scholars a week to comment briefly on some up-to-the-minute media text as a means of opening discussion about the issues it presents for media scholars, students, practitioners, and activists.

Note: And our most recent project, inTransition, is a collaboration with Cinema Journal featuring videographic film criticism — video essays, that is, that make use of the form in thinking about the form.

Note: But one of our key interests in building MediaCommons was thinking about the social connections it could promote among scholars in the field, getting those scholars in communication with one another, discussing and possibly collaborating on their work. To that end, we focused the platform around a peer network that enables scholars to use their profiles to gather together the writing they’re doing across the web and to provide citations for offline work, creating a digital portfolio that provides a snapshot of their scholarly identities.

## 3. the second book

Note: However, working on this project taught me several things that I sort of knew already, but hadn’t fully internalized, one of which is that any software development project will inevitably take far longer than you could possibly predict at the outset, and the second, and most important, is that no matter how slowly such software development projects move, the rate of change within the academy is positively glacial in comparison. And if I was going to make that change, I had to meet the academy where it was, and write another book.

Note: That book is Planned Obsolescence, which yes, I named after my blog. There had been several other books about the digital future of scholarship published in the preceding years, but most of them failed to fully account for the fundamentally conservative nature of academic institutions in the US and of the academics that comprise them. In the main, we are extraordinarily resistant to change in our ways of working; it is not without reason that a senior colleague once joked to me that the motto of my institution (one that might usefully be extended to the academy as a whole) could well be

## “we have never done it that way before”

Note: “we have never done it that way before.” Or, as Donald Hall has put it,

> “While we are very adept at discussing the texts of novels, plays, poems, film, advertising, and even television shows, we are usually very reticent, if not wholly unwilling, to examine the textuality of our own profession, its scripts, values, biases, and behavioral norms.”

— Donald Hall

Note: scholars often resist applying the critical skills that we bring to our subject matter to an examination of “the textuality of our own profession, its scripts, values, biases, and behavioral norms” (Hall xiv). This kind of

## self-criticism

Note: self-criticism doesn't come naturally to those of us who have been privileged enough to succeed within the existing system -- for us, at least, things seem to work perfectly well. But for others, of course, maybe less so, and so changing our ways of doing research, our modes of production and distribution of the results of that research, may well be crucial to the continued vitality of the academy —

## change

Note: and yet none of those changes can possibly come about unless there is first a profound change in the ways of thinking of scholars themselves. Until scholars really believe that publishing in new forms is as valuable as publishing in conventional ways — and more importantly, until they believe that their institutions believe it, too — few will be willing to risk their careers on a new way of working, with the result that that new way of working will remain marginal, undervalued, and risky.

So Planned Obsolescence focused not on just the set of technological changes necessary to allow academic publishing to flourish into the future, but

## social

## intellectual

## institutional

Note: the social, intellectual, and institutional changes that these new technologies require. In order for new modes of communication to become broadly accepted within the academy, scholars and their institutions must take a new look at the mission of the university, the goals of scholarly publishing, and the processes through which scholars conduct their work.

## 4. peer review

Note: And it’s the structures of peer review that I argue we need to begin with, because peer review is in some sense the sine qua non of the academy. We employ it in almost every aspect of the ways that we work, from hiring decisions through promotion and tenure reviews, in both internal and external grant and fellowship competitions, and, of course, in publishing. The work we do as scholars is repeatedly subjected to a series of vetting processes that enable us to indicate that the results of our work have been scrutinized by authorities in the field, and that those results are therefore themselves authoritative.

## but

Note: But I also want to suggest that the current system of peer review is in fact part of what’s broken. There’s a rather extraordinary literature available, mostly in the sciences and social sciences, on the problems with conventional peer review, including its biases and its flaws. Everyone I know has had direct, personal experience of those flaws — the review that misses the point, the review that must be personally motivated, or perhaps worst, the review that we never even get to see. And for such an imperfect system, peer review as we know it requires an astonishing amount of labor on our part, for which we can never receive “credit.” And so when Matt Kirschenbaum says that

Note: "what ought to count is peer review and scholarly merit," I agree, but at the same time feel quite strongly that the system of peer review that we know today could be vastly improved — particularly in a networked environment. The placement of peer review prior to selection for publication in the traditional print-based process indicates that it serves a largely

## gatekeeping

Note: gatekeeping function, one that allows certain kinds of academic discourse to thrive while other kinds are excluded. This kind of gatekeeping is arguably necessary in print, in order to cope with the scarcities of print’s economics — only so many pages, in so many books and journals, can be published each year. In the digital, however, this kind of scarcity is over. Because anyone can publishing anything online — and, from a perspective that values the free and open communication of the products of scholarly research, not only can but should — we face instead a overwhelming plenitude. And as we've seen in the last year, that plenitude can lead to a lot of crap in the system. But what we need to develop is not a means of applying the current system of peer review to new modes of online work in order to

## create artificial scarcity

Note: create artificial scarcity and keep the crap out, but instead a net-native system that can help us to

## cope with abundance

Note: cope with abundance. As it is, increasing numbers of scholars are either self-publishing their work via their blogs or are sharing work through a number of online scholarly networks, and in many cases, these publications are having a greater

## impact

Note: impact than their traditional peer-reviewed publications are. It’s certainly true in my case: all of my first citations, lecture invitations, and other forms of public recognition stemmed not from my journal articles or my book, but from the work I was doing on my blog. But of course these new modes of publishing demand some kind of assessment, even if that assessment comes after the fact. For that reason, peer review online might fruitfully include

## post-publication

Note: an open, post-publication means of review that doesn’t determine whether a text should be published (after all, the stuff is already out there) but rather represents how it has been (and how it should be) received, what its place in the ecosystem of scholarly communication is, and what kinds of responses it has provoked. Such a system would shift the center of gravity of peer review for online scholarship from gatekeeping

## conversations

Note: to facilitating more fluid and productive conversations amongst peers — and, not at all incidentally, a system in which the work of reviewing itself becomes visible as work, and the reviews themselves become part of the scholarly record. We might think of this as a system of

## “peer-to-peer review”

Note: “peer-to-peer review,” one that focuses on providing a post-publication mode of filtering the wealth of content that is shared online. After all,

## filters

Note: we need those filters, because despite what I said earlier, scarcity does linger in internet-based communication — it’s just that, for the most part, what has become scarce is time and attention, rather than the materials of production. So we need systems that allow a community of scholars working with and responding to one another to guide one another to the best work being produced in their fields.

Note: In order to put my money (at least metaphorically) where my mouth was, I put the entire draft of Planned Obsolescence online for open review in 2009. The primary benefit of this process for me was the conversations that it inspired: not only was I able to get more feedback, from more readers, but I was able to see those readers arguing with one another about the text. It also created an advance interest in the book, which wound up selling way better than the press expected, despite the manuscript being openly available.

## open questions

Note: But the project opened up a lot of questions about scholarly communication that remain only partially resolved, questions including

## authorship

Note: the ways that the nature of authorship is changing in the wake of the digital, both because our attention is gradually shifting from a strict focus on

## products to processes

Note: the production and dissemination of individual products (like a book or an article) to a broader focus on facilitating the processes of scholarly work.

## individual to collective

Note: Our attention is also gradually shifting from the individual to the collective in that work, as our networked processes start to surface the inevitably, if often hidden, collaborations involved in all scholarship.

## 5. scholarly communities

Note: And this is how my current projects come about, as I work, on the one hand, on ways of building and facilitating the development of scholarly communities, and on the other hand, as I think about the ways of thinking -- the core values and principles -- that those communities require in order to thrive.

http://generousthinking.hcommons.org

Note: That latter project is my new book, Generous Thinking, which I'm once again putting through an open peer review process. I'm staging the review process a little differently this time, first inviting a group of about 40 readers -- my scholarly community -- to engage with the manuscript, and then opening it to the world. Comments remain open until the end of March, after which time I'll start revising.

http://hcommons.org

Note: The other project is Humanities Commons, which is the platform on which I'm hosting the review process. Humanities Commons is an open-access, open-source, not-for-profit network for scholars and practitioners across the humanities. We originally started developing the project during my time working at the Modern Language Association as a means of facilitating communication among MLA members, but in December 2016, we launched Humanities Commons as a way of creating collaborations across fields. Humanities Commons offers a wide range of ways for scholars to participate in group discussions, to create new collaborations, to develop a professional profile online, and to share their work with one another and with the world.

## scholarly communication lab

Note: So Humanities Commons is part social network, part blogging network, and part disciplinary repository. But in the background, we're thinking of it as a kind of lab space within which scholars, librarians, publishers, and many other humanities practitioners can experiment with the future of scholarly communication, helping figure out what formats and modes of engagement create the best possible work today. If you don't have an account there, I hope you'll do some exploring and think about creating one. And I'd of course be happy to help with that, or to answer any questions you might have.

## 6. etc.

Note: There are a lot of issues that I haven't really talked about today, including the importance of (and challenges around) open access, the changing business models of scholarly publishing, the role of and problems with disruptive networks like academia.edu, and so on. But perhaps I can leave things there and we can see where your thinking is headed?

# thanks.

[Kathleen Fitzpatrick](http://kfitz.msu.domains) // [@kfitz](http://twitter.com/kfitz) // [kfitz@msu.edu](mailto:kfitz@msu.edu)