28 KiB

We Have Never

Been Social:

Web 2.0 and What Went Wrong

Kathleen Fitzpatrick // hcommons.social/@kfitz

Reclaim Open // 6 June 2023

Note: Thank you so much -- I'm delighted to be here and to get to talk with all of you today about something that's been bothering me for the better part of fifteen years:

what happened to blogging?

Note: What happened to blogging? We heard a bit yesterday morning in the opening panel about the early excitement around blogging, and lots of us really want to figure out where that excitement went and whether we might get it back. There are lots of obvious answers circulating out there, but it's a question that I take seriously, and personally. Because blogging made my career. And I mean that literally: insofar as I have anything like a public presence today, it was created by blogging. Everything I have written, every project I've worked on, every job I've held, to one extent or another I owe to my blog. And so I take what's become of it in the years since pretty hard, and I want to spend some time digging into what went wrong, and to think with all of you about whether, and how, the particular magic that blogs created might be recoverable.

2003

Note: I'm going to begin this inquest by jumping 20 years backward, to 2003. I was an assistant professor of English and Media Studies at a small liberal arts college on the eastern edge of the west coast, right where the sprawl of LA county runs into the desert. I'd been out of grad school for five years, and I was struggling to get my first book published, feeling the deadline of my 2004 tenure review bearing down on me. Spoiler alert: I did receive tenure, as it looked at the time of my review as though I'd found a home for that book, though it ended up being declined at the eleventh hour because the press's marketing guys couldn't figure out how to sell it. It finally did come out from another press in 2006, thankfully, but it ultimately had a far smaller impact on my career than did the writing I had been doing online in the interim.

So, content warning: I’m about to make a lot of us in the room feel super old. But to paint the scene a bit: in 2003, LiveJournal and Blogger had each been around for about four years, and of course GeoCities for another five beyond that. These were a somewhat messy and anarchic set of tools and spaces that allowed users to build out forms of self-representation and community connection, bringing the ethos that had long been found in discussion spaces like USENET, IRC, and a range of MUDs and MOOs to the graphical windows of the web. LiveJournal and Blogger were also the leading edges of the transformation of the world-wide web from a relatively static service, presenting pages that lived on servers requiring both access and a certain degree of expertise in order to manage on the back end. Instead, these new applications embodied the principles of the "read-write web," which allowed users to interact with and add to web content via the front end.

“web 2.0”

Note: That "read-write web" was one feature of the complex of web-based applications that was in the early years of the 21st century turning the browser from a means of presenting static web pages into something far more dynamic. That more dynamic thing is part of what many of us originally understood the term "web 2.0" to mean. Credit for coining the term is usually given to Tim O'Reilly, who in 2004 hosted the first "Web 2.0 Summit" intended to explore what the web was becoming as it took flight from the ashes of the dot-com bust. Wikipedia, however, attributes the first use of the term "web 2.0" to Darcy DiNucci, in a 1999 article entitled "Fragmented Future."

http://darcyd.com/fragmented_future.pdf

http://darcyd.com/fragmented_future.pdf

Note: In this article, DiNucci describes the first-generation web as "essentially a prototype -- a proof of concept" for "interactive content universally accessible through a standard interface," but given that "it loads into a browser window in essentially static screenfuls," it was clear even then that it was "only an embryo of the Web to come." DiNucci went on to describe the many screens and devices that might interact with what she called "web 2.0" in the future (including your microwave, which might automatically seek out correct cooking times online), noting quite presciently the particular challenges that web publishing would face in encountering such a wide range of screen sizes and resolutions. What DiNucci did not include in this fragmented future was what would happen when the web browser did more than retrieve and display content, but rather allowed for the creation of that content in the first place.

https://www.openlinksw.com/blog/~kidehen/

https://www.openlinksw.com/blog/~kidehen/

Note: It took another few years before Kingsley Idehen, in 2003, wrote a blog post thinking about XML-based applications such as RSS and their potential for "the next generation web," saying "I refer to this as Web 2.0."

https://www.openlinksw.com/blog/~kidehen/

https://www.openlinksw.com/blog/~kidehen/

Note: That this post was followed a month later by another quoting Jeff Bezos on the "executable Web" and the rapidly expanding "Amazon web services" that were supporting a wide range of database-driven online retail sites points exactly to the problem of "web 2.0": the channeling of interactive creativity into business. (And if you need something to break your heart just a little bit this morning, try this on for size:

https://www.openlinksw.com/blog/~kidehen/

https://www.openlinksw.com/blog/~kidehen/

Note: That tiny text reads "Q: What benefit is Amazon.com getting from this? A: It's too early to say. It's certainly not a major source of revenue for us. But when people use our Web services, they give us credit for that. This turns out to be very helpful.")

http://www.web2con/web2con via the wayback machine

http://www.web2con/web2con via the wayback machine

Note: Sigh. In any case. By the time Tim O'Reilly and John Battelle took the stage for the opening keynote at that first Web 2.0 Summit, they were ready to outline a vision for the future of "the web as platform," starring a lot of folks looking to build "truly great companies" on top of it. And it's thanks to those folks, and their interest in platformization,

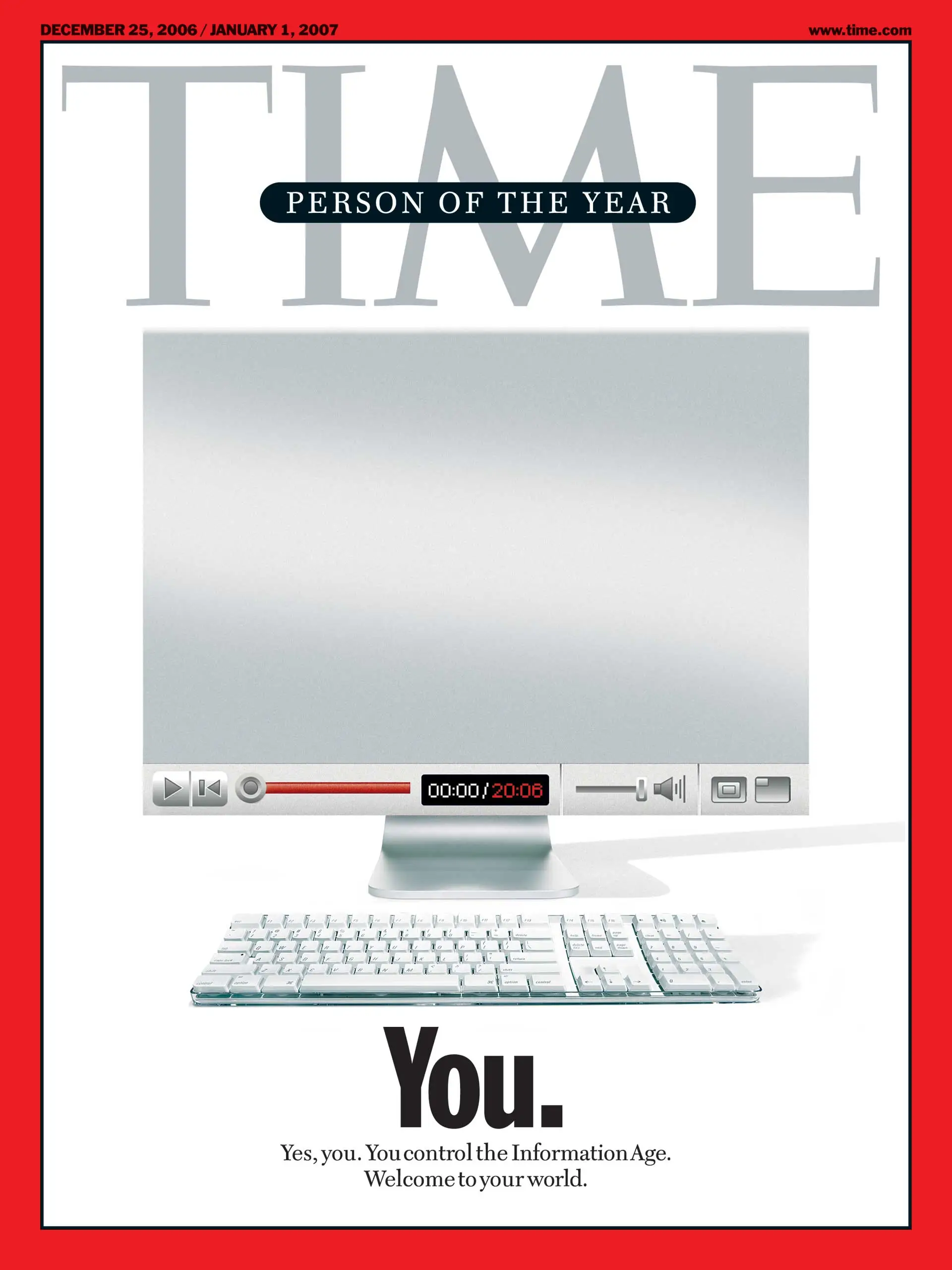

Note: that we'd find ourselves just two short years later honored as Time Magazine's Person of the Year, being told that we control the Information Age! The unbridled enthusiasm of the cover carries over into the story by Lev Grossman, though it's possible to see in the story an early hint of the forking paths that Web 2.0 presented. On the one hand, Grossman notes that the explosive growth in active, creative participation in online spaces was "a story about community and collaboration on a scale never seen before." On the other hand, the extent to which we -- you and I -- really control the world being built is uncertain, as Grossman hints at the importance of those building the platforms on which all this engagement was taking place, making it possible for "millions of minds that would otherwise have drowned in obscurity [to] get backhauled into the global intellectual economy."

I've gotten a bit ahead of the story I want to tell today, which is in large part about those forking paths, which point to community and collaboration in one direction and to the global intellectual economy in the other, and the fundamental failures that meant we were always destined to find ourselves lost in the latter even while we sought the former. So let's back up again, back to

2003

Note: 2003. As I noted, LiveJournal and Blogger had been actively feeding the read/write web for a few years, as had several other early blogging packages. Around that time, Matt Mullenweg and Mike Little decided to take the software they'd been using, b2/cafelog, which was about to be discontinued, and build something on top of it, releasing the first version of what they decided to call "WordPress" on May 27, 2003.

“blog”

Note: As for me, I first heard the word "blog" in a workshop at UCLA during the summer of 2001, when Jenny Bay, then an early career scholar of digital rhetoric, presented some early research questions she was exploring about the development of forms of online communication being popularized by folks like Jason Kottke. I remember being a bit puzzled at first, not just about how you'd go about building a website on which you could post regular updates about things you found of interest, but also, to be frank, about why you'd do so. I didn't see the appeal, at least not at first.

But the idea got stuck somewhere in the back of my head, and a year later, in June 2002, it resurfaced. I had just finished revising the manuscript for that first book, and I knew that it was probably going to be a year or two before anyone would be able to read it.

ahaahahhahahahahaahahahahhaahahha

Note: It turned out to be almost five years, which I don't know what I'd have done if I'd have known that at the time. But even given the deeply naive view of the scholarly publishing process that I was still clinging to at the time, I was antsy. I had Things to Say. And I was tired of waiting for my stuff to find its way to an audience. And one afternoon I was procrastinating by searching online for some old friends from grad school and I ran into this website that one of them had! It was one of those blog things! And it was funny, and smart, and people were reading it. And I knew they were reading it because they were responding to posts in the comments. And I thought, "oh man, that's it."

Note: So I figured out how to get an account with a web hosting service, and how to install Movable Type, and started blogging. My original site looked like this. I named it "Planned Obsolescence" as a bit of an inside joke -- the title of the ill-fated book I'd just finished writing was The Anxiety of Obsolescence, and the blog format felt like it provided a vehicle for, if not fame and fortune, at least a kind of obsolescence that I could control.

Note: Here's what my very first post looks like today. Since 2002 it's been migrated from Movable Type to ExpressionEngine to WordPress, from whoever my first hosting provider was to DreamHost to Reclaim, from plannedobsolescence.net to kfitz.info, and most recently from WordPress on Reclaim to a Jekyll-based static site hosted on GitHub. And yet, despite all of the web's evanescence, and despite my certainty that I was working in a form that was productive of obsolescence, this content remains -- remains accessible, remains available, remains alive.

When I started blogging, what I thought I was after was the instant gratification of publishing, the ability to push my words out to the world. All of the other thousands of words I'd produced were either stuck on my hard drive waiting for a press to agree to consider them, or languishing in journals that I wasn't sure anyone would ever read. The whole exercise of scholarly publishing as we knew it felt a whole lot like shouting down a well. But this! This blog thing would allow me to take charge of my own process, to push stuff out when I was ready.

conversation

Note: It turns out, though, that what I really wanted, deep down underneath the sense of being stifled, was the possibility of response. When you shout down the traditional publishing well, the only answer you really get is your own voice echoing back; the possibility that someone will read your article and cite it in their own, and then have that reply pushed through the publishing process is so slow as to have lost all traces of the conversational. The early world of blogging, however, was all about conversation. I'd post something, and someone would read it and leave a comment! Or, they'd read it and write a post in response, and link to mine in the process. There was an entire web of conversations taking place in the blogoverse, and through that web I found my way into a cluster of early literary and media studies bloggers, all of whom were writing and thinking together, lifting one another's ideas up and making them better along the way.

community

Note: This cluster of bloggers formed a community, one that I wasn't even really aware I needed back in my remote small liberal arts college bubble. That bubble was an awfully comfortable one, and yet I had no real collaborators inside it. Connecting online with folks who were pursuing questions related to my own produced a kind of engagement that was hard to sustain alone. And blogging turned out to be enormously productive for me: not only did the relationships built in that community evolve into several of the closest friendships I have today, but the writing I did on the blog led to every single idea I've had since, and every bit of recognition that my work has received.

Blogging in 2003 was the bomb, is what I'm trying to say.

but

Note: But. Alongside the creative ferment being produced by blogs in 2003, there were a few other developments happening. 2003 saw the launch of Friendster and MySpace. And then -- fairly quietly, at first -- this thing called FaceMash. These platforms billed themselves, to different extents, as ways to engage with your social networks online, which doesn't sound all that different from what the blog network I participated in did. Except, of course, that these were platforms, in which the accumulation of connections and competition for influence rather than the building of relationships became the point. By the time FaceMash turned into Facebook and started moving beyond Harvard's gates, "social networks" had become spaces for the accumulation of both social capital and venture capital. They were about YOU YOU YOU, and not at all about who we were together.

Note: Twitter was in this sense just another nail in the coffin, but I hold fast to the conviction that Twitter is what ultimately did blogging as I knew it in. Not just because it was so much quicker to spit out 140 characters than it was to write even a moderately considered blog post, and not just because that heightened sense of immediate gratification was coupled with knowing exactly how many people were following you, and thus (at least theoretically) how much of an "impact" your post about what your dog ate for breakfast was going to have, but also because one of its real benefits -- following people who posted links to cool stuff, including to your moderately considered blog post -- resulted in stealing the conversation away from blogs themselves. If someone had a response to the blog post you linked to on Twitter, they responded on Twitter, and that conversation rarely had a chance to develop in the ways it had in the comments, or in linked posts from other blogs. And worse, the fact that that conversation was taking place might not even be something that the original post author was aware of, or got to participate in.

Note: Of course, folks wrote WordPress plugins that attempted to repair that conversational leak, by aggregating tweets and republishing them as comments on the post to which they responded, not least the folks affiliated with the IndieWeb community, who argued for personally-owned alternatives to corporate platforms, ensuring that content you produce remained under your own control, published and connected where and when you wanted. While I'm a huge supporter of IndieWeb and its goals, I worry that focusing on ownership per se misses a part of what went wrong. The problem is not just that the platforms into which we poured our time and energy, our creativity, our representations of ourselves and our relationships with others -- it's not just that these platforms were corporate-owned. It's not just that those corporations had VCs to whom they had to provide quantitative proof of success. And it's not just that our relationships thus got caught up in the Silicon Valley cash nexus -- though all of that is demonstrably bad, too.

antisocial

Note: What's so antisocial about social media, rather, is mostly a radical misunderstanding of sociality itself.

“It’s the story of the hubris of good intentions, a missionary spirit, and an ideology that sees computer code as the universal solvent for all human problems.” (Vaidhyanathan, Antisocial Media 3)

Note: Siva Vaidhyanathan has described the history of Facebook by saying that "It's the story of the hubris of good intentions, a missionary spirit, and an ideology that sees computer code as the universal solvent for all human problems." That ideology assumes, among other things, that "society" can be represented coherently through the network graph of a highly individuated self and its accumulated connections -- that society is nodes and edges and that's about it. Fred Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture is pretty instructive on the ideological connections between the alternative communities of the ‘60s and the libertarian ethos of Silicon Valley, each of which focuses on freedom as something possessed by the sovereign individual. This understanding of freedom as negative liberty (freedom from regulation) rather than positive liberty (freedom to live fully) is a deep failure to reckon with the complexities of sociality. Real sociality is about human relationships and the contingent ways that individuals with different histories, cultures, languages, and experiences build a sense of mutual responsibility through ongoing conversation and endless negotiation – that failure results in, at best, a deeply impoverished network.

“the subjugation of the social to the technical“ (Eve, forthcoming)

Note: The Silicon Valley dream is a deeply libertarian landscape, one built on platforms that elevate the sovereign individual who can stand tall, without obligation. Martin Eve, in a forthcoming project that I was lucky enough to get a sneak preview of, thinks about this mode of platformization -- particularly with respect to the governance processes constructed through the blockchain and epitomized in the cryptocurrencies it supports -- as "the subjugation of the social to the technical." These technologies in fact represent the desire to eliminate the contingencies and complexities of the social and replace them wholesale with a form of technicality that can be individually optimized. This desire and the degree to which it has manifested in our social media platforms is what leads me to argue that

social media has never been social

Note: social media has never been social. It's not that things have recently gone wrong, with bad new overlords or dangerous political shenanigans. Everything that's wrong has been wrong from the start. "Social media" as we have known it has always been wholly geared toward the individual and the wants and desires of that individual as understood, processed by, and catered to through technology. Even more, the goal in that technical service to the individual has likewise never been social, no matter how much Silicon Valley rhetoric celebrates the ideal of global connection; the connectedness that these platforms is able to produce is between YOU, a pair of eyeballs, and the algorithm, which feeds you what it thinks you most want to see, in order to keep you sutured to the network itself.

- self-representation as performance

- engagement as confirmation

- interaction as data

Note: So, to dig in just a bit on the elements of the antisocial that makes social media what it is: (CLICK) First, the platforms encourage a presentation of selfhood that is less about representation than about performance, tailoring what is shared to the audience, each of whom is likewise engaged in a performance of self. (CLICK) Second, the interactions among those performed selves become a form of confirmation -- I see what you are presenting, and respond in the way I am supposed to -- rather than providing room for thoughtful exchange. And (CLICK) third, the platform ruthlessly tracks these interactions in order to figure out what you "like," for a value of like that most means stuff that you click on, with the goal of feeding more such stuff in order to prolong the connection -- where the connection is not between you and other humans engaged in a process of thinking together, but rather between you and a platform whose profits derive from your attention.

Note: There are so many things wrong with this that it's hard to know where to begin. When we are reduced to performing selfhood, when our conversations get turned into performances of connection, our online interactions far too often turn into knee-jerk reactions rather than considered responses. And on some level, this is what the platform wants. Whatever the algorithm behind social media platforms actually looks like when you dig into its code, it serves to produce the greatest rewards for the worst behavior, elevating posts that will produce reactions and thus feeding our worst impulses. As Siva Vaidhyanathan argues,

“Facebook is explicitly engineered to promote items that generate strong reactions…. Facebook measures engagement by the number of clicks, ‘likes,’ shares, and comments. This design feature – or flaw, if you care about the quality of knowledge and debate – ensures that the most inflammatory material will travel the farthest and the fastest.” (Vaidyanathan, Antisocial Media 6)

Note: READ SLIDE. The point is to keep you glued to the interface, to keep the dopamine hits coming. It is not only not engineered to create a sense of social connection or responsibility to the actually existing humans on the other side of those interactions -- it in fact functions to break any such sense of sociality, except insofar as it confirms our own performances.

grrr

Note: I could go on about this for quite a while, but I think I’ve said enough to convey the depth of the grudge that I bear toward Twitter and Facebook and all of the other social media platforms that together undermined what my small community of bloggers was building together. I have to acknowledge a couple of things here, though. First, Jessa Lingel reminds us to ask, however much corporate media platforms have done to gentrify the internet,

“Was the internet ever really ungentrified? The short answer is, no. There was no golden age when the internet was blind to race, class, and gender, no magical era when communities could thrive without corporate interference and a push toward profits.” (Lingel, The Gentrification of the Internet 15)

Note: READ SLIDE. Undoubtedly the portrait I have in my head of the wonders of 2003 skews rosy, as a highly educated upper-middle class white cis woman in the academy. Folks without my level of access and support may not have found the web such an easy place to find a home. It’s likewise important to remember the extent to which social media has been important for people who are marginalized or isolated, people who cannot safely be themselves in their families and communities. Many, many people have found support and comfort, and have developed real meaningful relationships that began on these platforms. And I have been able to keep in touch with old friends I’d never have seen otherwise. I have been able to see my nieces and nephews grow up. And social media networks have the potential to provide millions and millions of users with access to news and information. Of course, how good that news and information is, and how much I really get to know about those old friends, and how my nieces and nephews might feel about the pictures their parents are sharing, remains a real question.

responsibility

Note: The other thing I have to acknowledge, as plainly as I can, that I own some of the responsibility for what social media did to my blog, and to the community I was part of. I mean, I fell for it! I let the immediacy and the reach and the metrics turn my head and pull me away from the work I was doing. And I let it happen in part because, to be frank,

work

Note: the blog was hard work. It required a lot of time and attention to think through posts and make them worth sharing. It required real engagement with what other writers were posting, and a real willingness to think through their ideas and contribute something to the conversation. Blogging required real work – in the same way that real sociality requires real work – and however immediate blogging’s gratification seemed in comparison with writing (and god forbid trying to publish) an academic book, it had nothing on the nonstop dopamine fountain that was Twitter. So I let myself get pulled away into social media, and so did most of my blogging friends.

where are we now?

Note: But over the last ten years, to one extent or another, nearly all of us have found ourselves in a love/hate relationship with Twitter and Facebook, and lots of us have been looking for more satisfying alternatives. Several of us are part of a small, private Mattermost community that I host, one that is utterly closed and will remain so. Some of us have left Twitter for Mastodon, including the smallish but open instance that my colleagues and I at Humanities Commons are hosting (at hcommons.social – you’re welcome to join us there!) . And a few of us keep doing what we can to bring blogging back, to use the web spaces that we own and control to do longer-form, less noisy work.

go back

Note: So if this talk is going to close with anything like a call to action for those of us here, it’s for each of us to go back and see if we can recover the best of 2003, and infuse it with what we’ve learned in the two decades since. What I want to get back to is partly the kind of personally owned infrastructure advocated for by the IndieWeb folks, and partly the decentralized communities of Mastodon. But it’s also an understanding of the web as a space for the kind of inventiveness that doesn’t have a business model behind it. Creativity without venture capitalists. Thoughtful conversation. The potential for building real relationships. That’s what was best about the web that was – less that the infrastructure was personally owned or decentralized (though that too!), than about its potential for real sociality and the joint invention and experimentation it inspired, the ways that new features got hacked together with duct tape and baling wire rather than with the polish that VC funding brought. I mean, Webrings! Blogrolls! Pingomatic! And RSS!

RSS

Note: RSS, the little engine that could of the web. It’s been pronounced dead more times than I can count, and it just keeps coming back. And so in this vein, I want to close by bringing up one of my web heroes,

Note: Brent Simmons, the developer behind NetNewsWire. His website, inessential, makes clear that the app – a super clean RSS reader – is and will remain 100% free. Simmons originally launched NetNewsWire in 2002; it was acquired by NewsGator in 2005 and then by Black Pixel in 2011. Sometime in about 2015, Brent started working on a new RSS reader, Evergreen, but in 2018 he reacquired the intellectual property involved in NetNewsWire, merged it with the new product, and returned it to active development. So: NetNewsWire, a free and open tool for engaging with the free and open web. And as he notes, he will not accept money for the app – but he points to a number of ways to support it:

https://github.com/Ranchero-Software/NetNewsWire/blob/main/Technotes/HowToSupportNetNewsWire.markdown

https://github.com/Ranchero-Software/NetNewsWire/blob/main/Technotes/HowToSupportNetNewsWire.markdown

Note: The first of those being “Write a blog instead of posting to Twitter or Facebook”! If you don’t do it for me, do it for Brent, and for NetNewsWire. Take your work back. Keep it not just free and open, but genuinely social. Use your work on the web to share, to think, to discuss, to learn. Reclaim your intellectual property, and your intellectual production, for all of us.

thank you

Kathleen Fitzpatrick // hcommons.social/@kfitz

Note: Many thanks!