31 KiB

Digital, Public, Scholarship

Sustainable Infrastructure for the Future of the University

Kathleen Fitzpatrick // @kfitz // kfitz@msu.edu

Note: Before I get started, I want to thank Cris for inviting me to speak here with you today; I'm delighted to have this chance to celebrate the launch of the Digital Scholarship Studio and Network with you, and to talk a bit about the kinds of work, and the kinds of futures, that an institutional structure like this makes possible.

Note: Part of what I hope to address today stems from my recent book, Generous Thinking. The book as a whole argues that the future of the university as we have known it depends heavily on rebuilding relationships of trust between our institutions and the publics that they serve. The book addresses lots of aspects of those relationships and ways they might be fostered, but the key bit for today is that the networks and spaces that support digital scholarship are crucial to building and maintaining connections with a range of broader publics in the context of the work we do on campus.

background

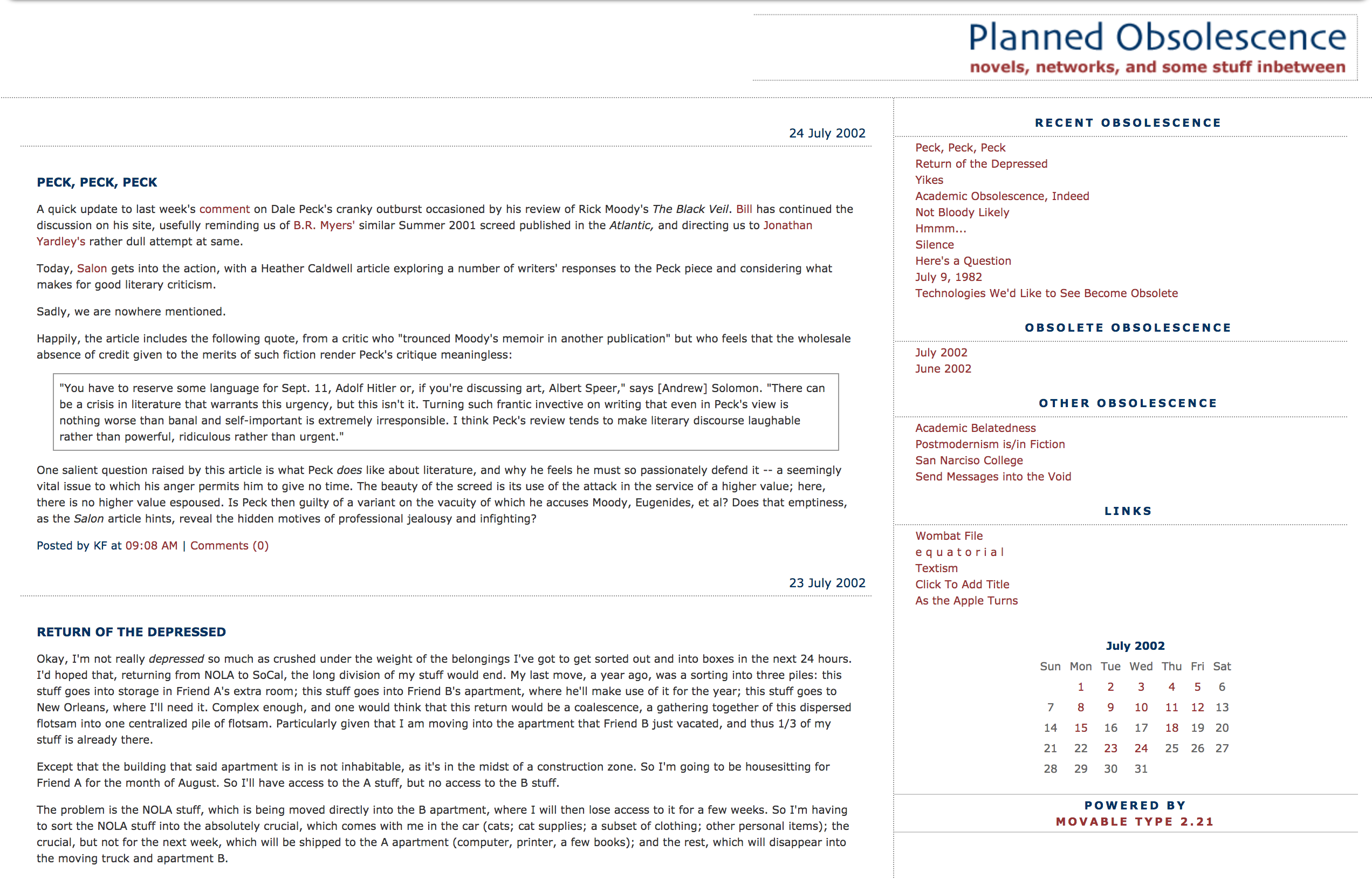

Note: I come to this work through a slightly idiosyncratic path. Back in 2002, I'd just finished the long process of revising my dissertation into my first book, and I was feeling stifled: years of work were stuck on my hard disk, and there seemed the very real possibility that no one else might ever read it. (I wasn't wrong -- it took another four years to get the thing published, for a lot of complicated reasons.) And then I stumbled across the blog of a friend from grad school; it was funny and erudite, and it had an audience. People read it, and I knew they read it because they left comments responding to and interacting with him. And I thought, wow, that's it.

Note: My blog, which I started out of the baldest desire to get someone somewhere to read something I wrote, wound up doing something more interesting than I expected: it helped me build a small community. I found a number of other early academic bloggers, all of whom were in ongoing comment-and-crosslink conversations. Those relationships, which opened out into a growing network of scholars working online, were crucial to me as a somewhat isolated assistant professor. I had struggled to make the intellectual and professional connections that might help my writing develop, and it was the blog that provided the first real opportunity. Even more, posts I published there were the first pieces of my writing to be cited in more formal academic settings.

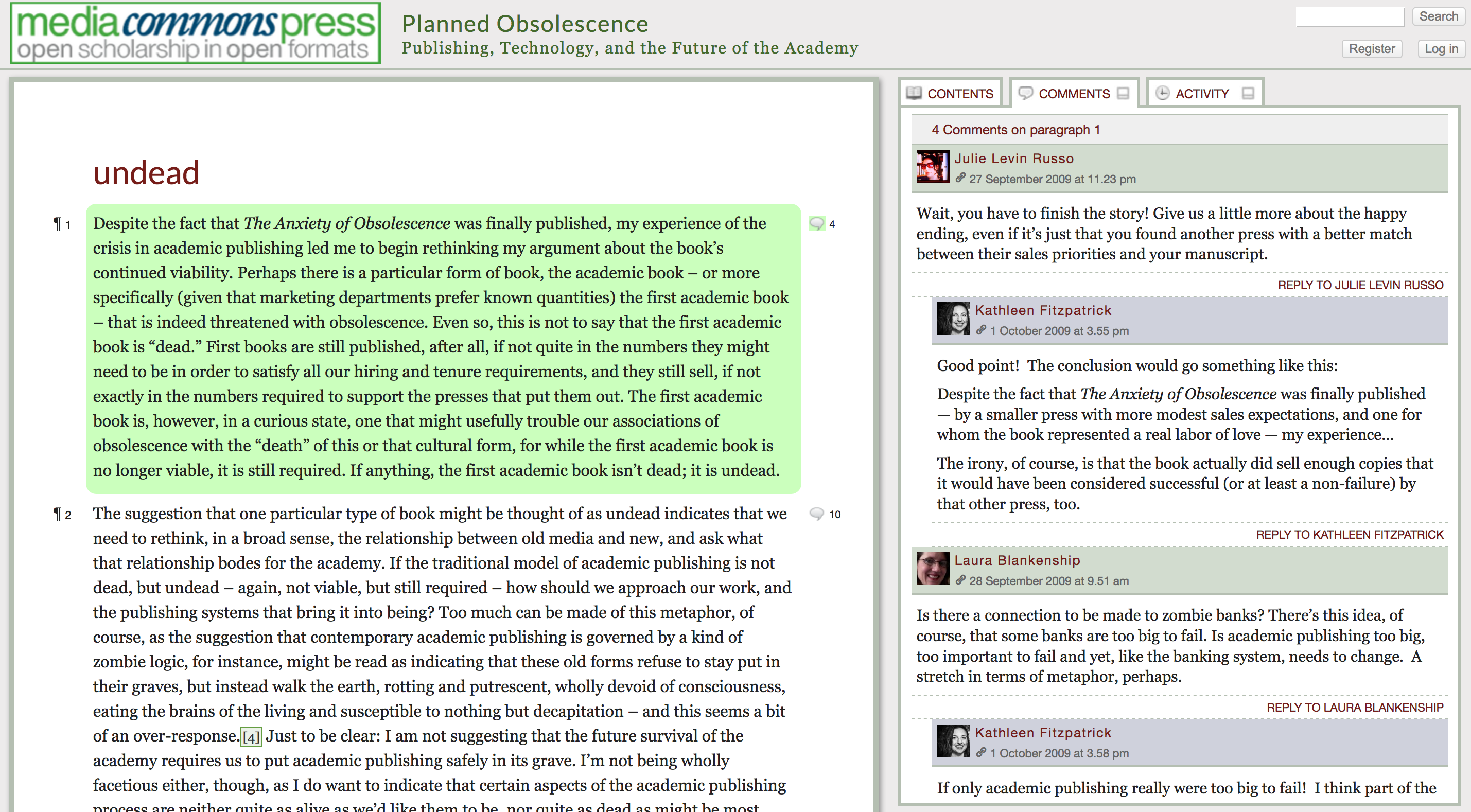

Note: So fast-forward to the moment in 2009 when I'd just finished the draft of my second book. Rather than simply have the manuscript sent out for anonymous peer review, I asked my press to let me post the draft online for open comment too. I get asked a lot about that decision, especially how I worked up the courage to release something unfinished into the world where anyone could have said anything about it. The truth of the matter is that the risks didn't figure into my thinking. What I knew was that there were a lot of folks out there, in many different fields and kinds of jobs, with whom I'd had productive, engaging interactions that contributed to the book's development, and I wanted to hear their thoughts about where I'd wound up. I trusted them to help me--and they did, overwhelmingly so.

2009

Note: It's important to acknowledge the entire boatload of privilege not-thinking about the risks requires; I was writing from a sufficiently safe position that allowing flaws in my work-in-progress to be publicly visible wasn't a real threat. It's also not incidental that this was 2009, not 2019--a much more naive hour in the age of the Internet. The events of the last few years, from GamerGate to the 2016 presidential campaign and beyond, have made the risks of opening one's work up online all too palpable. But my experiences with the blog, with the book manuscript, and with other projects I've opened to online discussion, still leave me convinced that there is a community, real or potential, interested in the kind of work I care about, willing to engage with and support that work's development. And--perhaps most importantly today--willing to work on building and sustaining the connections that make up the community itself.

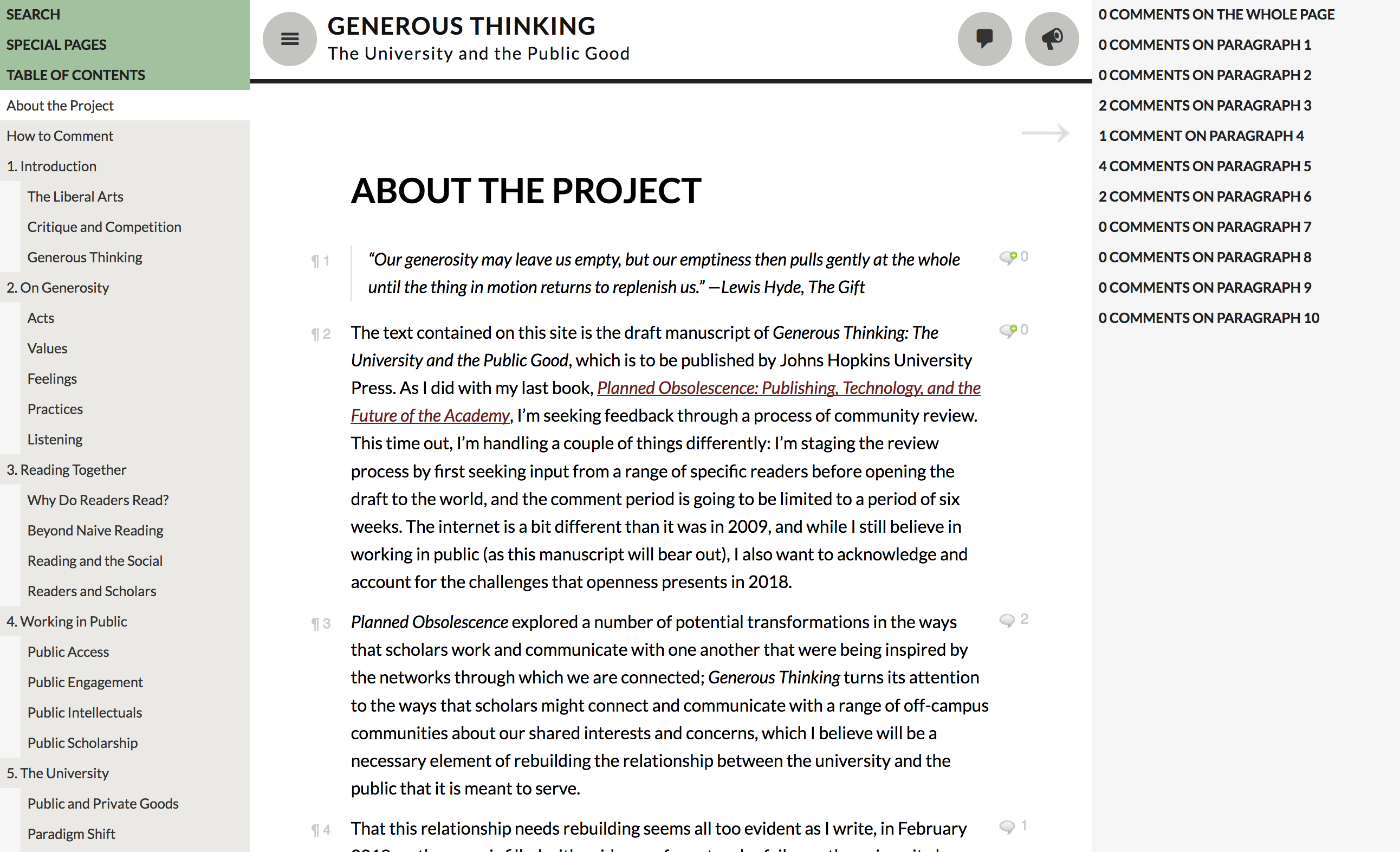

Note: I tested that belief in 2018 by opening the draft of Generous Thinking to a similar open review. Between early February and the end of March, I staged a process in which I first invited a group of readers to spend two weeks reading and commenting on the manuscript, after which I opened the project to the world. In the end, 30 commenters left a total of 354 comments (and prompted 56 responses of my own), giving me a rich view of the revision process that lay ahead. It wasn't all rainbows and unicorns: there are a few comments that sting, and a few spots where I wish the gaps in my thinking had been a little less visible, but I'm convinced that the book is better for having gone through this public process.

public

Note: So what I'm focused on is the ways that a digital scholarship network like this one can can enable scholars to build new kinds of of communities, within our fields, with other scholars in different fields, and with folks off-campus who care about the kinds of work that we do. By finding ways to connect with readers and writers beyond our usual circles of experts, in a range of different registers, and in ways that allow for meaningful multi-directional exchange, we can create the possibilities for far more substantial public participation in and engagement with the humanities, and with the academy more broadly. We can build programs and networks and platforms that do not just bring the university to the world, but that also involve the world in the university.

obstacles

Note: There are, of course, real obstacles that have to be faced in this process. Some of them reflect the communication platforms that we use today. Blogs don't readily produce the same level of engagement that they did in the early 2000s. In part this has to do with their massive proliferation, and in part it has to do with the dispersal of online conversations onto Twitter and Facebook and other networks. As a result, online communities of readers and writers are unlikely to develop spontaneously; instead, building community around online work has to be far more deliberate, reaching out to potential readers and participants and finding ways to draw them, and ourselves, back into sustained conversation.

trolls

Note: And of course the nature of internet discourse has changed in recent years as much as has its location. Trolls are not a new phenomenon, by any means, but they certainly seem to have multiplied, and the damage that they can inflict has escalated. Taking one's work public can involve significant risk--especially where that work involves questions of social justice that are under attack by malevolent groups online, and especially for already marginalized and underrepresented members of the academic community who open up engagement with an often hostile world.

no easy answers

Note: I do not have easy answers to these problems; I do not have a perfect platform to offer, and I do not know how to fix the malignant aspects of human behavior. Countering these destructive forces requires advance preparation and focused responses. Ensuring that public discourse about scholarly work remains productive requires a tremendous amount of collective labor, and the careful development and maintenance of trust, in order to create inclusive online communities that can be open to, and yet safe in, the world. But there are several other challenges that I want to explore a bit today, challenges that are about the ways that we as scholars do our work, the ways that we can draw a range of broader publics to that work, and the ways that we can ensure that the work we do together is supported in an ongoing way.

access

Note: The first is the need to ensure that the work we do can be discovered and accessed by any interested reader, and not just by those readers who have ready entry to well-funded research libraries. It should go without saying that it is impossible for anyone to care about what we do if they cannot see it. And yet, perhaps because we assume we are mostly writing for one another, the results of our work end up overwhelmingly in places where it cannot be found--and even if it is found, where it cannot be accessed--by members of the broader public.

accessibility

Note: The second challenge lies in ensuring that the work is accessible in a very different sense: not just allowing readers to get their hands on it, but enabling them to see in it the things that they might care about. We often resent the ways that academic work gets "dumbed down" in public venues, but we might think instead about ways that we can productively mainstream our arguments, engaging readers where they are, rather than always forcing them to come find us, in our venues and on our terms.

participation

Note: Beyond access and accessibility, however, if we hope to engage the public with our work, we need to ensure that it is open in the broadest possible sense: open to response, to participation, to new kinds of cultural creation by more kinds of public thinkers. In other words, we need to focus not just on the public's potential consumption of the work that is done by the university, but also about potential modes of co-production that involve communities in the work of the university. Such collaborations might serve as a style of work that our universities can fruitfully model for the rest of our culture: new modes of scholarship done not just for but with the world.

networks

Note: Networks for digital scholarship have the potential to create the conditions for greater access, for greater accessibility, and for greater public participation in the work that we all do as scholars. By encouraging this kind of work, I don't mean to suggest that there is no room for more traditional modes of internal exchange among field-based experts; there is, and should be. But the twenty-first century university must provide means by which the results of those exchanges can become part of the larger cultural conversations taking place around us. Our work doesn't need to address or engage everyone at all times, of course, but different aspects of our work might engage with different audiences at different moments. Knowing how to think about those audiences--and, indeed, to think about them not just as audiences, but as potential interlocutors--is a crucial skill for today's scholars, and a skill that needs to be cultivated and supported.

open access

Note: The simplest way of making more scholarly work more available to the public is by making that work available through open access venues. There's a long history to the open access movement, of course, and in the book I dig into that history and the ties the movement created between its altruistic goals -- establishing and supporting a globally equitable mode of distributing knowledge -- and it more pragmatic arguments about the impact that public access might have on the advancement of research. The key point is that what's good for the public turns out to be good for scholarship, too.

engagement

Note: If we publish in ways that enable any interested reader to access our work, that work will be more read, more cited, creating more impact for us and for our fields. Making our work more openly accessible enables scholars in areas of the world without extensive library budgets, as well as U.S.-based instructors and students at undergraduate teaching institutions and secondary schools, to use it. Making our work openly available also allows it to reach other interested readers from across the increasingly broad humanities workforce who may not have access to research libraries. All of this can produce an expansion in our readership and an expansion in our influence -- an unmitigatedly good thing.

resistance

Note: Any yet, it's clear that we often resist opening our work to broader publics, for a variety of reasons. Many of us keep our work restricted to our own discourse communities because we fear the consequences of making it available to broader publics--and not without justification. The public often seems determined to misunderstand us, to interpret what we say with focused hostility or, nearly as bad, utter dismissiveness. Because the subject matter of much of the humanities and social sciences seems as though it should be accessible, our determination to wrestle with difficult or highly politicized questions and our use of expert methods and vocabularies can feel threatening to many readers. They fail to understand us; we take their failure to understand as an insult. (Admittedly, sometimes it is, but not always.) Given this failure to communicate, we see no harm in keeping our work closed off from the public, arguing that we're only writing for a small group of specialists anyhow. So why would public access matter?

why

Note: It matters because the more we close our work away from the public, and the more we turn away from dialogue across the boundaries of the academy, the more we undermine the public's willingness to support our research and our institutions. As numerous public humanities scholars including Kathleen Woodward have argued, the major crisis facing the funding of higher education is an increasingly widespread conviction that education is a private responsibility rather than a public good. We wind up strengthening that conviction and worsening the crisis when we treat our work as private. Closing our work away from non-scholarly readers might protect us from public criticism, but it can't protect us from public apathy, a condition that may be far more dangerous in the current economic and political environment. The risks are real, especially for scholars working in politically engaged fields, but only through dialogue that moves outside our own discourse communities will we have any chance of convincing the broader public, including our governments, of the relevance of what we do on campus.

generosity

Note: And of course engaging readers in thoughtful discussions about the important issues we study lies at the core of the academic mission. It is at the heart of our values. We don't create knowledge in order to hoard it, but instead, every day, in the classroom, in the lecture hall, and in our writing, we embrace an ethic of generosity, of paying forward knowledge that we have received as a gift. We teach, as we were taught; we publish, as we learn from the publications of others. We cannot pay back those who came before us, but we can and do give to those who come after. Our participation in an ethical, voluntary scholarly community is grounded in the obligations we hold for one another, obligations that derive from the generosity we have received.

prestige

Note: Okay, idealistic, right? And that kind of idealism is all well and good, but it doesn't adequately account for an academic universe in which we are evaluated based on individual achievement, and in which prestige often overrides all other values. I dig into the institutional responsibility for and effects of that bias toward prestige in another part of the larger project; here, I want to think a bit about its effects on the individual scholar, as well as that scholar's role in perpetuating this hierarchical status quo. Surveys of faculty publishing practices indicate that scholars choose to publish in venues that are perceived to have the greatest influence on their peers, and that influence is often understood to increase with exclusivity. The more difficult it is to get an article into a journal, the higher the perceived value of having done so. This reasoning, though, too easily shades over into a sense that the more exclusive a publication's audience, the higher its value. // This is, at its most benign, self-defeating; if we privilege exclusivity above all else, we wind up undermining our work's potential cultural impact; as David Parry has commented,

"Knowledge that is not public is not knowledge."

Note: "Knowledge that is not public is not knowledge." It is only in giving it away, in making it as publicly available as possible, that we produce knowledge. As it is, most of the players involved in the production of scholarship have always been engaged in a process of "giving it away": authors, reviewers, scholarly editors, and others involved in the process have long offered their work to others without requiring direct compensation. The question, of course, is how we offer it, and to whom.

gift economy

Note: In fact, the entire system of scholarly communication runs on an engine of generosity, one that demonstrates the ways that private enterprise can never adequately provide for the public good. So rather than committing our work to private channels, signing it over to corporate publishers that profit at higher education's expense, how might all of the members of the university community--researchers, instructors, libraries, presses, and administrations--instead work to develop and support a system based on our highest values? What if we understood sustainability in scholarly communication not as the ability to generate revenue, but instead the ability to keep the engine of generosity running?

free

Note: It's important, however, to distinguish between this call to generosity and the injunction to work for free produced by the devaluing of much intellectual and professional labor within the so-called information economy. A mode of forced volunteerism has spread throughout contemporary culture, compelling college students and recent graduates to take on unpaid internships in order to "get a foot in the door," compelling creative professionals to do free work in order to "build exposure," thereby restricting opportunity to those who can already afford to seek it. And of course there are too many academic equivalents: vastly underpaid adjunct instructors, overworked graduate assistants, an ever-growing list of mentoring and other service requirements that fall disproportionately on the shoulders of junior faculty, women faculty, and faculty of color.

labor

Note: Labor, in fact, is the primary reason that we can't just simply make all scholarly publications available for free online. While the scholarship itself might be provided without charge, the authors have by and large been paid by their employers or their granting organizations, and will be compensated with a publication credit, a line on a c.v., a positive annual review outcome. Reviewers are rarely paid (almost never by journals; very modestly by book publishers), but receive insight into developing work and the ability to shape their fields and support their communities by way of compensation. But there is a vast range of other labor that is necessary for the production of publications, even when distributed online: managing submissions, communicating with authors; copyediting, proofreading, website design and maintenance, and so on. We need to understand that labor as professional too and compensate it accordingly.

responsibility

Note: So where I am asking for generosity--for giving it away--it is from those who are fully credited and compensated: those tenured and tenure-track faculty and other fully-employed members of our professions who can and should contribute to the world the products of the labor that they have already been supported in undertaking. Similarly, generosity is called for from those institutions that can and should underwrite the production of scholarship on behalf of the academy and the public at large. It is our mission, and our responsibility, to look beyond our own walls to the world beyond, to enlarge the gifts that we have received by making them public. Doing so requires that we hold the potential for public engagement with our work among our highest values, that we understand such potential engagement as a public good that we can share in creating.

interest

Note: But there are steps beyond simply making work publicly available. Critics of open access often argue that the public couldn't possibly be interested in scholarly work; they can't understand it, so they don't need access to it. Though I would insist that those critics are wrong in the conclusion, they may not be wrong in the premise; our work often does not communicate well to general readers. And that's fine, to an extent: communication within a discourse community plays a crucial role in that community's development, and there must always be room for expert-to-expert communication of a highly specialized nature. But that inwardly-focused sharing of work has been privileged to our detriment. Scholars are not rewarded--and in fact are at times actively punished--for publishing in popular venues. And because the values instantiated by our rewards systems have a profound effect on the ways we train our students, we build the wall between academic and public discourse higher and higher with every passing cohort.

public-facing

Note: Of course, many scholars have recently pushed against this trend by developing public-facing publications that bring the ideas of humanities scholars to greater public attention, venues like the Los Angeles Review of Books and Public Books. There are also a host of other kinds of digital projects that demonstrate the ways many scholars are already working in multiple registers, engaging with multiple audiences. These venues open scholarly concerns and conversations to a broader readership and demonstrate the public value of scholarly approaches to understanding contemporary culture.

writing

Note: But if we are to open our ideas to larger public audiences, we need to give some serious thought to the mode and voice of our writing. Because mainstream readers often do not understand our prose, they are able to assume (sometimes dismissively, and sometimes defensively) that the ideas it contains are overblown and unimportant. And this concern about academic writing isn't restricted to anti-intellectual critics. Editors at many mainstream publications have noted the difficulty in getting scholarly authors to address broader audiences in the ways their venues require. We have been trained to focus on complexity and nuance, and the result is often lines of argumentation, and lines of prose, that are far from straight-forward. Getting past the accusations of obscurity and irrelevance requires us to open up our rhetoric, to demonstrate to a generally educated reader how and why what we do matters.

accessible

Note: Again, not all academic writing needs to be done in a public register. But we would benefit from doing more work in ways that are not just technically but also rhetorically accessible to the public. And we are all already called, to varying extents, to be public intellectuals. Our work in the classroom demonstrates that translating difficult concepts and their expression for non-expert readers is central to our profession. This act of translation is an ongoing project that we might take on more broadly, getting the public invested and involved in the work taking place on campus and thereby building support for that work. But for that project to be successful, scholars need to be prepared to bridge the communication gaps, by honing our ability to alternate speaking with one another and speaking with different audiences.

learn

Note: So we need to think a bit about what we need to learn in order to do that kind of work. Public-facing writing--as many editors of mainstream intellectual publications would note--is very different from academic writing, and by and large it is not something scholars are trained to do. But numerous initiatives are working to help scholarly authors focus and express the ideas contained in their scholarly publications in ways that help broader audiences engage with them. Ideally, this kind of writing should become part of graduate training across the university.

publics

Note: However, a key component of the work of the public intellectual is not simply addressing but actually helping to build a public in the first place. Nancy Fraser long since noted the fragmentation of contemporary public life into a "plurality of competing counterpublics." We need to consider the possibility that, in retreating from direct engagement with the public, we have actually contributed to the public's fragmentation. As Alan Jacobs has noted, "Subaltern counterpublics are essential for those who have never had seats at the table of power, but they can also be immensely appealing to those who feel that their public presence and authority have waned." The retreat of scholars into private intellectual life has produced a tighter sense of community and the comfort of being understood, but at the cost of withdrawing scholarly issues and perspectives from public view, and with the result of further fragmentation of the public itself. If we are to return to public discourse, if we are to connect with--and perhaps even be responsible for creating--a range of broader publics, we're going to have to contend with those publics' multiplicity, even as we try to draw them into dialogue.

work

Note: Most importantly, perhaps, we need to recognize that scholars who work in public modes are doing work that is not just public, but also intellectual. Our processes of evaluation and assessment too often shove things that don't meet a relatively narrow set of criteria for "research" into the category of "service." As a result, when scholars make the transition to more public prose, their work is frequently underrewarded, if not actively derided, back on campus. Writing for the public is often assumed to be less developed, when in fact it's likely to have been far more stringently edited than most scholarly publications. Worse yet, the academic universe too often assumes that a scholar who writes for a public market must "dumb down" key ideas in order to do so. If we're going to make publicly engaged digital scholarship genuinely sustainable, we have to ensure that it's properly respected, and properly rewarded, so that the focus can genuinely be placed on engaging with the communities the work is trying to reach.

understanding

Note: This is in some ways the heart of the problem: we too often do not know how to reach those publics, because we don't fully understand them. And, as I argue at length in the larger project, this is in no small part because we spend a bit too much time talking and not enough time listening to them. We need to make room for the public in our arguments, and in our prose, but we also need to understand those arguments and that prose as one part of a larger, multi-voiced conversation. And this is the key: having found a way to connect with a broader audience, having helped to transform that audience into something like a public, how do we then activate that public to work on its own behalf?

public scholarship

Note: Here is where our working in public--creating public access, valuing public engagement, becoming public intellectuals--transforms into the creation of a genuinely public scholarship, a scholarship that is not simply performed for the public but that includes and is in fact given over to the publics with whom we work. In public scholarship, members of our chosen communities enter into our projects not just as readers but as participants, as stakeholders.

citizen humanities

Note: Recent experiments in "citizen science" provide some potentially interesting examples, projects like Galaxy Zoo that go beyond crowd-sourcing, enlisting networked participants not just in mass repetitive tasks but in the actual process of discovery. But what might the citizen humanities look like? It might look like museum exhibits such as Pacific Worlds at the Oakland Museum of California, which engaged members of local Pacific communities in the planning and development processes. It might look like The September 11 Digital Archive, developed by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University and the American Social History Project, which presents first-hand accounts of the events of that day, along with photos, emails, and other archival materials from more than 150,000 participants. It might look like the Baltimore Stories project at UMBC, which used humanities scholarship as a convening force to bring community organizers, educators, and non-profit organizations together to explore narratives of race in American life. What these projects have in common is that each of them explores a cultural concern of compelling interest to the public that the project engages, precisely because that concern belongs to them. The work involved is theirs not just to learn from but to shape and define as well. Engaging these publics in working with scholars to interpret, understand, and teach their cultures and histories can connect them with the projects of the university in ways that might help encourage a deeper understanding of and support for what it is that the university does, and why.

"peers"

Note: By working in publicly engaged ways, and by bringing those publics into the self-reflexive modes of humanities- and social science-based critique, we have the potential to produce a renewed conception of how intellectual life operates in contemporary culture -- but that renewed conception is going to require us to be open to a new understanding of the notion of our "peers." Open, public scholarship might lead us to understand the peer not as a pre-existing credential but instead as a status that emerges through participation in the processes of a community of practice. Changing this definition has profound consequences not just for determining whom we address within that label but also who considers themselves to be a part of that category. Opening the notion of the intellectual, or the peer, to a much broader range of forms of critical inquiry and active project participation has the potential to reshape relations between town and gown, to lay the groundwork for more productive conversations across the borders of the campus, and to create an understanding of the extent to which the work of the academy matters for our culture as a whole.

networks

Note: And much of that work begins with projects like the DSSN, which provides not just a place where new forms of collaborative, public scholarship can be invented but the networks through which it can be realized. An institutional structure like the DSSN enables us to ask what might be possible if we were to open up our scholarly practices up to real public engagement, to deep interdisciplinarity, to new modes of working. How can networks like this enable public universities like UB to more genuinely focus on the mission of bringing knowledge to the people of the state? How might a network like this draw public support back to the institution by demonstrating the extent to which the work done here is intended for, in dialogue with, and in the service of the public? For public universities to win back public support, they must find ways like this--structurally, strategically, at the heart of not just the mission statement but of the actual mission--to place publicly engaged work at the top of its priorities. And that starts in places like this, where scholars can come together to explore new work in and with the public.